West Africa

I travelled in West Africa through the diversity of Morocco, Mauritania and Senegal in 1996, traveling through that conflicted space where the Arab world meets Black Africa. Interestingly, landscape seems to have assumed that uneasiness as the Sahara threatens to swallow the Sahel.

Todra, Drums, and East and West

In Marrakesh they say the city is made of four colors: blue of sky, white of mountain, green of fields and red of walls. Todra Gorge, however, comes only in shades of red. Arriving in Todra Gorge from the small town of Tinerhir we hit rain that down poured into the oasis valley and hung a double rainbow above the ochre-colored escarpments that stand above the town. The rain placed the sweetness of moist earth on the dry air and the rain hazed the dark green palms and fields.

Todra Gorge itself loomed like a deep slash in the Moroccan High Atlas Mountain range, the stone red as if we’d cut into the flesh of the earth. Our vehicle forded Todra stream, then continued on to the Hotel Yasmina that has ruddy ramparts like the Berber settlements in Tinerhir and the other oasis towns in this high desert country. We stayed in a dorm provided with Moroccan couches and pillows as beds.

That night, after a dinner of stir fried vegetables and goat we adjourned to the café where Mohammed, the proprietor, and his brothers, entertained us with Berber music with guitar and drums ranging from one 18 inches across, to porcelain, gourd-shaped drums held between the knees. All had skin heads that occasionally needed to be heated by the fire.

The café was a long, narrow room with cream walls, arched windows and couches and low tables along both sides. At one end stood an ornately tiled counter and at the other a large iron and brick fireplace jutted into the room and smoked profusely. A T.V. sat incongruously on a table in the corner and two large, ornately patterned, red and black Berber carpets covered the cool tiles.

The music made my blood pump, my foot tap on the tiles and my shoulders sway. We clapped with them, struggling to capture the Moroccan clapping style that results in a high, clear, popping tone. One of the young men began to dance; a square-shouldered, slim-hipped, handsome fellow, who was slightly intoxicated from smoking hashish. The dim light, the music, the smoke and the drink continued for hours and I could imagine long nights in Berber tents and the men dancing. Of course women wouldn’t be there, because this is a man’s culture. But here, in this hotel, we’re allowed.

Finally Mohammed and the others rested their hands and asked for a song from us in trade. In typical western fashion the group of us couldn’t seem to get our act together to select a song. As a result we ended up with portions of songs from three different continents (Australia, Europe and North America) and a helpless collapse into laughter.

Perhaps this is a comment on the West – we can only half-finish what we start, and that not well, because it takes too long to get it right. But it was a wonderful evening, the night slightly cold, the room warm and heavy with wood and cigarette smoke, the old man in striped robe and turban clapping in the corner, the man with the peaked djellaba smiling and offering me a seat, the laughter of friends and comrades across cultures.

We were terrible as a singing group.

February 1996

Mauritania – Abandoned

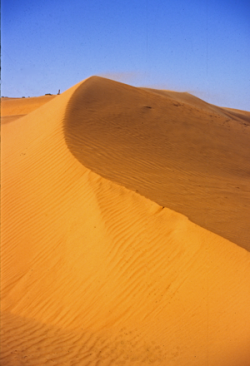

Three thirty pm and we have sat here in the harsh sun and sanddunes at the border between Mauritania and the disputed lands of the Western Sahara

since before lunch, all because one of our party has a Visa with improper dates. The border is comprised of low stone walls to mark where one country ends and another begins. That and the burned out remains of a jeep that we’ve been told is all that remains of two foolish French tourists who decided to run the border. They hit a landmine and one died.

So we wait, having left the handsome Moroccan soldiers hours ago and now face a thin, unbending Mauritanian Corporal who seems to demand respect he isn’t getting from our leader. We end up abandoning our travel companion at the border with water and food and the promise we’ll somehow sort this out at the next town – or the capital, Nouakchott.

So we enter a country that seems intent on death and endings. Where once we thought we were untouchable, Mauritania has shown us otherwise.

Wind-worn outcroppings. Stunted bushes and rock carved like coral. Desert of bone-white shells left high and dry when the ocean receded. Pink dunes that slide into turquoise ocean, both intent on inundation of the other. Beaches littered with a long line of dead tuna, sea turtle and gull, while Arab-style dhow boats cruise the fishing grounds off shore and flamingos soar northward. The light falls at night, too hard and fast to believe, yet the tops of the dunes lifting seem to hold light longer, creating ghostly apparitions across drifts and hollows. The wind in the truck’s metal work hoots like Berber music, as if their inspiration was the wild music of the Jafhya or Irifi winds.

Nouâdhibou, our first stop, lay beside the sea, a huddle of nondescript buildings. After many meetings with police and military, our friend was released, but his Visa still was a problem and had to be dealt with in Nouakchott, so we flew southward, across a landscape where the stones all appeared to be fossilized remains of ancient beasts and the dunes rose above the hard pan like islands in a mirage sea. The sun turned the sand and trees into a stark land of abbreviated silhouettes and wind and heat. We drank mint tea brewed in a red tea pot with our guide, a berber man in rich blue robes who placed stunted grass around the base of his tent each night as if he hoped that would help hold it in place. The rest of us weren’t wise enough.

At Nouakchott the delays caused by our companion’s detention cut short our stay, so we remained only long enough to deal with his Visa issue and then ran south toward Senegal, driving like the wind. Our Visas were all running out of time and who knew what would happen if we didn’t cross the border in time.

Southward the endings that abide in the Mauritanian desert shows their devastating nature. Here, the dunes rose up above the small, blue and white painted villages. A man stood beside the carcass of his cow. Dunes inundated fields and the trees planted to stop the dunes movements. Palms were swallowed inexorably and blue and white houses had empty doors and windows that the dunes flowed through.

Farther south, where the Senegal River formed the border, the estuary grasslands – home to great herons, egrets, Egyptian ibis, fish eagle, hawks and kestrel – were aflame to make farm land for the people forced to abandon their villages to desert. Smoke pillared into a sky filled with marabou storks, their black and white forms reflecting apricot in the late afternoon sunlight, as they lifted like embers on a carrion wind.

At the border we had to bribe the guards with antibiotics after they demanded all the women be paraded before them. We abandoned the country before it showed its force to us again.

March 1996

Ile de Goree, Senegal – A Place of Music

Goree Island sits just off the coast of Dakar, the capital of Senegal, in a turquoise bay. The island’s fame comes from its history as the last part of Africa too many slaves saw before the Portuguese stole them away to America. Today the island has its museum to the slave trade, but it also holds a thriving colony of musicians and other artists.

Goree contains many impressions. I wanted quiet to sit and write, but every time I sat I was surrounded by children or young men or women wanting me to take their picture. Some are precious like Darria Boussou, the young woman who braids hair into elegant cornrows for tourists. She and I spoke for a time after I shielded her from a Chinese film crew that wanted to capture her finery. Together, we travelled back and forth to the mainland twice, because she lives there with her parents after divorcing the older man her parents arranged for her to marry. Now she seeks a jeune home – a young man – we both laughed at this.

Arriving in Goree from the ferry that sails from Dakar, the place is pristine as a park with none of the twisted polio beggars one deals with in Dakar. In the early morning smiling women in bright dresses and headscarves sweep the Goree streets clean. At the top of the island waits the Blais Fall enclave of drummers. They will tell you about their drums – they are very good – and let you wander around their living area amongst the remains of the old Portuguese armaments. Here, amid Baobab trees, a huge cannon sits facing the mainland.

Goree has goats on the roadway, teak trees with leaves fading, Baobab trees everywhere and kestrel hawks flying – I continually felt the shade of wings overhead. Children – the Petite Ecole – with rows of dark heads turned toward the voice of the teacher. Thin cats feeding on garbage dumped at the end of the street to await disposal. Blue waves. Arched doors and windows and pirogues (African boats) that are blue on blue ocean.

After a dinner of Poulet Massau – chicken in peanut sauce followed by beignet (cake), I walked the island taking photos in the sweet light of sunset and talking to a young Senegalese man who spoke French, Spanish and English, I heard drumming mysteriously across the island. Where from? I followed the sound and found my way to the island’s open-air theatre where they practiced a play. I’d been told about the event earlier in the day, but hadn’t believed the man. The play – more a story told with drums and song – took place in an old, stone-walled amphitheatre, that might have been ruins, with a stone slab as a stage in front of a wall of arches and stairs. Through the openings you could see the huge roots of trees had grown into the wall and draped foliage over the street beyond.

An actress stood on the upper level reciting her lines (My Africa) until the drums began and the dancers started. Lithe bodies of the young women and girls dancing – the drums and a huge guitar-type instrument with a male singer. The singing was outstanding, but the feel of the songs – the joy – the exaltation of the dancers, the movement of the bodies that were as slim hipped and waisted as the drums, made a kaleidoscope of sound and movement.

The light turned the neighboring church golden, the sky bluer and kestrels floating on updrafts overhead, made the twilight something that glazed the evening with the sense of the unexpected. Perhaps the most fun was the audience of youngsters I sat with. Our seat bounced. Our feet tapped. Our shoulders swayed and I couldn’t get this big grin off my face.

I spent the night in the home of Khadijatou, another young woman I met on the island, in her room on the second floor on a hard mat where I couldn’t sleep. The next day I left Goree with the children calling goodbye.

They called me friend of Darria.

March 1996