The World Has Three Points

I mentioned last week how the ancient Egyptian, Eratosthrenes, used a column and a shadow as two sides of a triangle to estimate the size of the earth, which shows the importance of geometry to cartography. Nowhere was this more evident than in mapping the earth, where triangulation, (the process of determining the location of a point by measuring angles to an unknown point from known points at either end of a fixed baseline), was literally used to measure the location of everything in relation to everything else.

I mentioned last week how the ancient Egyptian, Eratosthrenes, used a column and a shadow as two sides of a triangle to estimate the size of the earth, which shows the importance of geometry to cartography. Nowhere was this more evident than in mapping the earth, where triangulation, (the process of determining the location of a point by measuring angles to an unknown point from known points at either end of a fixed baseline), was literally used to measure the location of everything in relation to everything else.

Geometry and triangulation had actually proven themselves previous to Eratosthrenes. They’d been used to measure the heights of the pyramids and had also had been highlighted by the ancient Chinese as an important principle of mapmaking. Unfortunately this wasn’t well known in Europe even though the Arabic influence brought such surveying methods into old Spain. Instead, Europe was still transcribing tourist tales and fanciful stories onto paper and selling these for parlor display based on their beautiful illuminations, rather than spending their time surveying the landscape.

Apparently the first European to get serious about the use of triangulation was a Dutchman named Gemma Frisius who suggested using triangulation as a means to pinpoint the location of places on maps. The technique gradually spread through the 1500s, but it wasn’t until the 1600s that Europe got serious. A Dutchman named Snell began the process of surveying the landscape with a chained line of triangles (much like the triangles the American flag is folded into)across the countryside for a distance of 70 miles. The use of Snell’s process led to a rise in the quality of the Dutch maps and, in comparison, the decline of French maps into dependence upon engraving and elegant color as their selling feature – all well and good as a parlor adornment, but not what you want if you actually want to do something with the map you made.

Enter Guillaume Deslisle: In the late 1600s this young Frenchman began to change maps from things of the arts to matters of science. At a time when the great rulers such as Louis XIV knew little about the countries they ruled, he began to use triangulation surveys to permanently shift and fix continents and islands on the map, and even settled the age-old argument about the length of the Mediterranean Sea (41 degrees). The work of Deslisle and his kin led to the first mapping of Russia, or Muscovia as it was known at the time, and eventually influenced the French Minister for Home Affairs and advisor to Louis the XIV, Jean Colbert, to push for the mapping of France.

Enter Guillaume Deslisle: In the late 1600s this young Frenchman began to change maps from things of the arts to matters of science. At a time when the great rulers such as Louis XIV knew little about the countries they ruled, he began to use triangulation surveys to permanently shift and fix continents and islands on the map, and even settled the age-old argument about the length of the Mediterranean Sea (41 degrees). The work of Deslisle and his kin led to the first mapping of Russia, or Muscovia as it was known at the time, and eventually influenced the French Minister for Home Affairs and advisor to Louis the XIV, Jean Colbert, to push for the mapping of France.

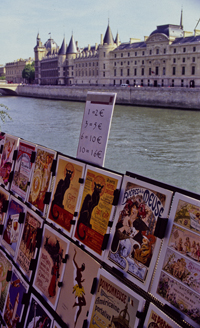

In 1663, Colbert ordered that each French province’s maps be examined to see if they were of sufficient quality. If they were not, qualified surveys were to be undertaken. This eventually led to Abbe Jean Picard overseeing the first precisely measured chain of triangles and topographical surveys around Paris – the two preliminary foundations to accurate mapping. The extension of this process led to France being mapped and became the standard practice for scientific mapmakers. It was used in the cartographic expeditions used in Lapland and Peru discussed in my last cartographic blog, in mapping the Himalayas, the English countryside and, the Grand Canyon and everywhere else in the world.

In 1663, Colbert ordered that each French province’s maps be examined to see if they were of sufficient quality. If they were not, qualified surveys were to be undertaken. This eventually led to Abbe Jean Picard overseeing the first precisely measured chain of triangles and topographical surveys around Paris – the two preliminary foundations to accurate mapping. The extension of this process led to France being mapped and became the standard practice for scientific mapmakers. It was used in the cartographic expeditions used in Lapland and Peru discussed in my last cartographic blog, in mapping the Himalayas, the English countryside and, the Grand Canyon and everywhere else in the world.

But the work of Deslisle and Picard had unforeseen impacts. Like the magic in my books, the new maps seriously revised France’s boundaries and coastal outline. The world’s shape was changed again – all because of three points.

But the work of Deslisle and Picard had unforeseen impacts. Like the magic in my books, the new maps seriously revised France’s boundaries and coastal outline. The world’s shape was changed again – all because of three points.