Maps and Spies

In one of my last posts (here) I wrote about how Sir Francis Drake may have been the real first discoverer of the Pacific Northwest coast, and how this fact was likely kept under wraps by the British government because of the potential for Spanish spies. Maps and spies have gone hand-in-hand for years and are still important in modern battles. I recently picked up the book Swan Song and the opening scene is the President looking at spy satellite images (maps) of Russian Territory. Spies and maps. That’s what this post is about.

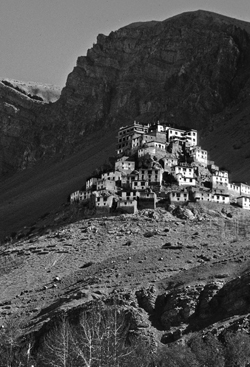

Of course spy satellites weren’t always around, but spies were, and they have played an important role in the Great Game of Asia (the name given to the period between 1813 and 1907 when the Brits and Russians duked it out over influence and ownership over Central Asia). Being able to map an area and to gain control over important vantage points, rivers, towns and countries was all part of ‘the game’. The Survey of India I mentioned here, was all part of the British Raj’s need to know about and control their holdings.

But they ran up against a barrier – the physical boundary of the Himalayan Mountains and the geopolitical border with Tibet that had been closed by order of the Chinese Emperor. Although Europeans had sighted the heights of K2 and had scaled peaks only slightly less tall than Mount Everest, they hadn’t been able to map Tibet because of the Chinese border that specifically excluded Europeans. As a result, a captain of the Indian Survey, Thomas G. Montgomerie, decided to train and send disguised native agents into the mountains. Only two men passed the rigorous training: cousins Nain and Mani Singh.

In 1865 they went on their first mission through Nepal and into Tibet to try to reach Lhasa. The two became separated on their journey. Mani made it into western Tibet and returned with some mapping information, but it was Nain who managed to make it to Lhasa. Along the way he was robbed, but managed to retain his survey instruments. Trained to take even paces as his means of measuring distance and using a 100-bead rosary to keep track of his pace-count, he eventually entered the fabled city disguised as devout pilgrim. There he chanced public beheading by taking night-time measurements of altitude and latitude using mercury he poured into his begging bowl.

When he thought people were becoming suspicious of him, he left the city with a Ladakh caravan and headed west along the great Tibetan river, the Tsangpo. Along the way he mapped the river’s course and kept up his careful measures before finally escaping one night to make his way back across the Nepali border. He’d travelled 2,000 miles and mapped it all and returned with descriptions of Lhasa and the first reasonable placement of it on the map.

Nain’s accomplishment was followed by similar mapping parties, not all of which ended well. One agent travelled into northern Afghanistan and was murdered in his sleep. Another returned to Lhasa and back to India with data on almost 48,000 square kilometers of previously unmapped territory. A nephew of Nain’s continued the work and travelled for nearly six years in the mountains. He’d mapped a caravan route to China as well as the headwaters of the Mekon, the Salween and Irrawaddy rivers.

More impressive still, is the adventure of Kinthup, another native trained to survey the mountains. In 1880, he and another man were sent into the mountains to answer the question of whether the Tsangpo River became the Brahamputra. He braved the mountains and escaped after being sold as a slave by his ‘partner’ on the venture, but still managed to complete his mission in a feat that became legendary to Survey of India.

But it was only in 1911, after the Great Game was over, that the mapping of the Himalayas was completed, when the British joined their surveys with those of the Russians they had so long fought against. But it was brave native spies like Nain Singh and Kinthup who did the work for us and brought Lhasa and the Himalayas into the known world.