Bhutan: How Gross National Happiness Made Me Cry

Sometimes… sometimes this world can be so darned hard to be in—like reading about the death of the last male northern white rhino, or that 18 of the Tigers ‘rescued’ from a Thai temple ended up dying. And then there’s the whole darn political situation where nobody seems to speak the whole truth.

But other times the world can be such a giving place that it overwhelms. That was my experience in Bhutan.

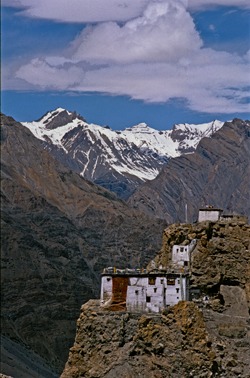

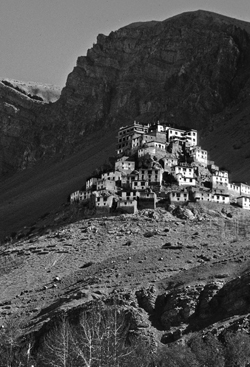

As I mentioned in a prior post, Bhutan is a Buddhist country. It isn’t a big country. It isn’t particularly modern in the way places like London, New York, or even Bangkok might be, but it’s a country that seems to understand the concept of ‘enough’. It might not be a wealthy country (up until this year it’s biggest source of revenue was tourism), but the government has decided not to rate the well-being of the country not on gross domestic product (in other words, how much does the country produce or earn each year), but instead they assess the country on Gross Domestic Happiness.

I’m not quite sure how they measure this apparently quite ‘ephemeral’ concept, but I have to say that the country seems to be doing quite well. Some of it seems to be the personal realizations of the citizens that they can have ‘enough’—maybe not from driving for the ‘high life’, but from something else. For instance, the country has put a lot of energy into education and has a well-educated middle class. This has lead to many young people leaving their traditional country villages for the city leading to pressure on Thimpu and Paro (the two main cities) and some concern for the farming tradition of the country. What did the country do? It offered sizeable subsidies for the well-educated young people to return to farming—and its working!

Bhutan is also a country that is trying hard to balance growth with protection of the environment. Compared to most countries around the world, Bhutan has actually seen an increase in the its national forest cover and it does things like set aside an entire fertile valley floor in order to preserve the habitat of the rare black-necked crane. Pretty progressive.

At the same time, tradition is everywhere. Come to a bridge, a river confluence, or mountain pass, and you find yourself amongst the fluttering host of red, yellow, green, blue or white prayer flags. Tradition says that with every gust of wind, the prayers connected to the flags are sent skyward to the benefit of the prayer flag’s patron. You become a patron by deciding to put up the flags but you’ll also see clusters of white prayer flags on poles that are raised in remembrance of the newly dead.

While I was in Thimpu, the capital, I had the chance to visit a Bhutanese astrologer who informed me that:

- I was a Fire Monkey (they use the Chinese astrological calendar)

- That I was going through a couple of bad years, and

- That there were flags that I could hang to help me get through this tough patch.

Given the astrologer was exactly right about the couple of bad years, I took the prayer flags he recommended and thought that I would hang some in Bhutan and some when I returned home. My kind and oh-so-knowledgeable guide, Kuenzang Norbu, researched dates that were bad to hang flags, and our wonderful driver, Tenzin Norbu (no relation) actually asked his father to research my best and worst days of the week.

Not long afterward, we were traveling over one of Bhutan’s many high passes where the wind rarely ceases. The peaks of the pass were a mass of poles bearing crowds of fluttering flags and I knew immediately that this was where I had to hang my flags. Wonderful Tenzin helped me sort through them and then our entire group climbed the hill with me and helped hang my flags.

Whether it was for my benefit or whether it was because we all received the benefit of hanging those flags in the wind, the giving nature of everyone involved (foreign photographers and Bhutanese hosts alike) left me quite astounded.

So, I stood in amongst all those windswept prayers and cried.