Lost in Bali

We’ve been in Bali ten days now and it has been a wonderful lesson in exploration—both sensory and experiential. For instance, at the moment I’m in my bed listening to a thundering downpour and the quintessential sound of gamelan music played for a Balinese shadow puppet show.

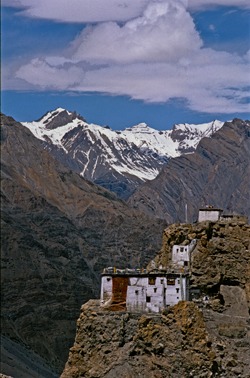

But not every experience has been quite so mesmerizing. At least they haven’t all been quite so easy to enjoy. Take for instance my first experience at my current guesthouse in the tourist mecca of Ubud. Ubud sits on the lower slopes of Bali’s central mountains and is a mecca for artists from around the world. Think wood and stone carving, silver smithing, weaving, painting and just about anything else you can imagine. We arrived at this guesthouse and our host knew of my interest in photography, so he immediately told me that there was a temple ceremony occurring that afternoon at a local community—come see him at three pm and he’d arrange for me to attend.

I showed up with camera in tow and the only way to get there was via motorcycle—him driving and me on the back. Let me just say that my distrust of motorcycles goes way back to my teenaged years and age and wisdom has only confirmed that opinion.

But it was a temple ceremony and I was new to Ubud. Who knew whether I’d get such a chance again. So I slung my leg over the motorbike behind him and drove—sans helmet because he didn’t want to have to carry an extra helmet back—to somewhere in Bali.

And he dropped me off.

Yes, I had his email and phone number on Whatsapp. Yes, I knew the name of the guesthouse and generally where it was in Ubud. But that was all. And oh, yes, I know how to say hello and thank you in Balinese.

But there was this temple ceremony, that it turned out I couldn’t attend because I didn’t have a proper sarong…

So I hung around outside with the parents with unruly children and the Balinese marching band (think gongs, conches for blowing, and lots and lots of drums.) Luckily, the Balinese are big on processions, because after what sounded from outside the walls like a lovely ceremony, the dignitaries left (would you believe it was the royal family of Ubud?) and were followed by a flood of people.

I ran up the road to get a better view and what followed was a village procession. The photos in this post tell the tale. A non-marching band. Children dressed up like princesses. Women carrying offerings on their heads and men carrying even larger offerings on platforms. And all the people in their finest sarongs and sashes. They marched up the road with so much laughter and friendship that I was swept along—until they reached another temple and I was shut out again.

Darned no sarong.

And then I had to figure out how to get home…

From somewhere in Bali.

P.S.

(Yes, after realizing that my Whatsapp messages were being routed via North America so there was a time lag, I finally contacted my wonderful host by phone and he sent his son to rescue me. So I am no longer lost.)