Faith, Maps and Portolan Charts

Okay, I’m anachronism. It’s Easter Sunday and so I’m writing about faith—well, a little bit of faith—faith and maps.

Okay, I’m anachronism. It’s Easter Sunday and so I’m writing about faith—well, a little bit of faith—faith and maps.

As I’ve said, I like maps and will continue to use them. Though many people are turning more and more to GPS systems in their vehicles, I still have my trusty book of street maps of the metropolitan area where I live. When I pull out my yellowing, dog-eared map book I’m reminded of the volumes of Portolan charts of old, that were the predecessors of the Mercator projection I spoke of HERE.

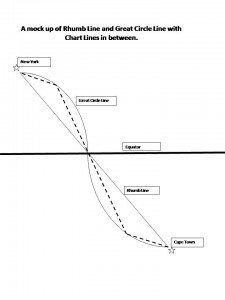

Portolan charts were mariner charts, used by sailors to navigate the Mediterranean and then the coasts of Africa and Asia. The earliest existing portolan chart dates from 1290, but records as early as 1270 talk of a captain pulling out charts to convince a frightened king that their ship really could reach land during a terrible storm. Portolan charts have distinctive features, most noticeably the rhumb lines and compass roses that gave sailors bearings to set their sailing headings. These rhumb lines set out the four cardinal directions and the principle wind directions (North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West and Northwest) as well as the eight half-winds (NNE, ENE, etc.) Portolan maps also had detailed, careful place names along the coast, color coding of places to show importance, and standard ways of showing rocks and shoals, while overemphasizing bays and headlands—all important information for sailors trying to reach safe harbor. This is very different from the predecessor of the Portolan, the medieval mappamundi , which generally had East at the top, and Jerusalem at the centre without any detail. The mappamundi were there to represent a way of thinking for the faithful; all they really needed to know was the location of Jerusalem in relation to where they lived. By contrast, the portolan set out in detail the way to make your way in the world.

Yes, there were issues with the portolan charts. They used a rough scale, but had none of the accuracy the Mercator Projection provided. Still, they served their purpose.

Yes, there were issues with the portolan charts. They used a rough scale, but had none of the accuracy the Mercator Projection provided. Still, they served their purpose.

No one knows who made the first portolan chart, but researchers have shown that those we know about were copied, some by tracing (they can tell by small pinpricks left in the vellum, and some by simple eyeballing). Portolan charts were also generally written on vellum—sheep or calf skin prepared in such a way that the narrow end of the beast (toward the neck) could fit the narrowing of the Mediterranean. The vellum could handle the rigors of sailing better than paper could and vellum could role up for easy storage or could be made into volumes of portolan charts. Of course, because they had different makers, different parts of the world were drawn using different scales which made it a challenge to draw up larger maps of the world.

But portolan fell out of use with the advent of the Mercator Projection because, while the portolan charts were good for the Mediterranean and coastal shorelines, they were not as good for great sea voyages where the Mercator Projection provided relatively easy ways to chart a route from places like South Africa to New York.

But portolan fell out of use with the advent of the Mercator Projection because, while the portolan charts were good for the Mediterranean and coastal shorelines, they were not as good for great sea voyages where the Mercator Projection provided relatively easy ways to chart a route from places like South Africa to New York.

So the beautiful, utilitarian portolan chart fell out of use, just like my map book has fallen out of favor in comparison to those tiny black box GPS units and smart phones that help gadget users to get from point A to point B. To me, it feels like civilization has taken a great leap forward by stepping back. No longer are we worried about great sea voyages (Mercator maps), or even the details of where such and such a place sits along the coast in relation to where we are (Portolan charts). Now we simply input our destination and trust the GPS to tell us which headings to take, much like medieval civilization trusted their priests to tell them how to live in relation to Jerusalem. Which makes me wonder whether we might have stepped right back to the days of the mappamundi, where our sense of direction is directly related to our faith—but today it’s our faith in technology.