Mapping Loss: Maps and the Enbridge Pipeline

Last week I wrote about how the cartographers of the early western mapping tradition created North America in the public’s imagination through their tales of the Garden of the World that awaited the person daring enough to travel westward, and through their splendid maps that unrolled the future in the shapes of the landscape.

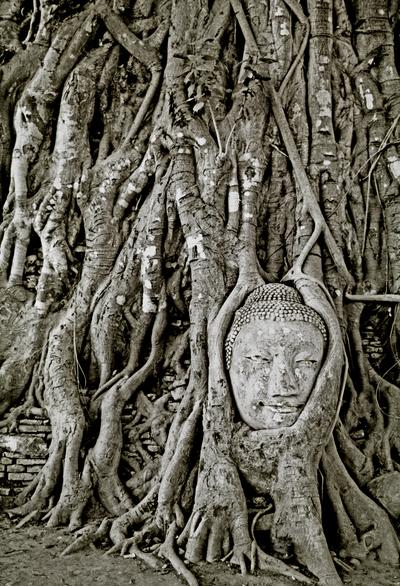

But maps also set out losses. Ancient maps show the destructive ebb and flow of empires across the landscape as mankind shifted capitals and allegiances or had them imposed by various leaders. We see Tyre and Babylon and Troy washed away by time, but maps of their greatness remain, some etched in stone, some recreated by scholars to hint at the greatness we have lost through time. The same can be said for the great maps drawn by Lewis and Clark and others, for as they rolled the country out for settlers, they marked horrible future losses of North America’s First Peoples. Indeed, you could say that the unfolding of the maps of North America rewrote reality from that of native people, to that of the settlers.

But maps also set out losses. Ancient maps show the destructive ebb and flow of empires across the landscape as mankind shifted capitals and allegiances or had them imposed by various leaders. We see Tyre and Babylon and Troy washed away by time, but maps of their greatness remain, some etched in stone, some recreated by scholars to hint at the greatness we have lost through time. The same can be said for the great maps drawn by Lewis and Clark and others, for as they rolled the country out for settlers, they marked horrible future losses of North America’s First Peoples. Indeed, you could say that the unfolding of the maps of North America rewrote reality from that of native people, to that of the settlers.

In more modern times we’ve seen maps used to show the devastating paths of tsunamis and the epicenters of quakes. Maps show us the destructive forces of nature, like the creeping dread of the Sahara desert, or the paths of hurricanes and tornados and the arcs of loss across the states where those killers touch down. Maps also portrayed manmade disaster like the destruction let loose by the Deepwater Horizon, as its killing oils reached the silver reed coastlines of the Gulf of Mexico. Maps of hydroelectric projects mark the loss of valley’s forests, and Indian villages with the blue lines of deep water.

Equally, or perhaps more, important maps show us future losses. Right now, in Canada, maps abound showing the proposed path of the Enbridge Oil Sands pipeline from the Alberta oil sands all the way across northern British Columbian mountain ranges and muskeg to a narrow fjord at a town called Kitimat on the Pacific Ocean. From there, supertankers will collect crude oil for the industries and cars of China.

Proponents of the pipeline speak of it as if it marks prosperity across this country, like a vein of money that will bring jobs in the construction phase and open the purse of China right into Canadian government coffers. But an overlay on that map also speaks of potential loss. Supertankers threaten to rewrite our coastlines from the pristine home of orca and sea otter, to the barrens left behind by oil spills. Broken pipelines threaten salmon spawning grounds and the haunts of those icons, the moose and beaver, not to mention the homes of the great, great grandchildren of those same First People we stole the continent from years ago.

The trouble is, most people just look at what is, and they don’t see the competing futures these maps propose anymore than people driving past a proposal sign for local development question the losses that development will cause. Those who propose the development see prosperity in new homes for sale and new retail stores. Whereas, reading the losses, I see the destruction of the trees and the birds and small animals that live within their green space.

So I’m suggesting we need to take the time to reread our maps and recognize the losses our development proposes. Otherwise we threaten to be like our forefathers and repeat their destructions. We need to listen to North America’s First People and remember the animals we share this earth with. Otherwise we threaten the very Garden of the World that caught settlers imaginations so many years ago. If we don’t, we’re likely to end up like the civilizations on those ancient maps – lost in time and remembered only for all the destruction we caused.