The inimitable Joanna Vandervlugt interviewed me about Beneath Malabar Nets

Check out the Podcast HERE.

Check out the Podcast HERE.

We spent our last week in India on the move. From Kanya Kumari we headed north again, toward our arrival spot of Chennai and Mamalapurum. We broke up our train trip halfway through at a city named Trichy to visit the Sri Rangnam temple, one of the largest temples in southern India—and probably the country. Sri Rangnam is 156 acres and has seven concentric enclosures and 21 magnificent towers (gopuram.) The temple is a world heritage site that has been restored. According to the signs, they had to dig it out from underneath modern structures and have the modern structures removed.

Trichy—at least the part where we stayed and the parts around the temple, seemed like a working man’s city. There were hotels and there were tourist groups, but mostly it was low structures and local bazaars and markets and the people who lived and worked there. A surprise I had in Trichy was the number of Moslem women who had taken the veil. Full burka’s were far more common than the other places we had visited in Southern India which could indicate a higher Moslem population or a more conservative one.

Of course, the sense of Trichy being a working man’s city could be a result of taking local buses around the city instead of rented cars. The busses were an experience in and of themselves. Think of J.K. Rowling’s ‘night bus’ in the Harry Potter series that changes shape to fit between other busses as it careens around the city. The Trichy buses can careen just the same way. Inside, the women sit on the right side of the bus, the men on the left. When no seats are left, people just cram inside.

The Sri Rangnam temple is as massive as a small city. It has six concentric walls, the outer wall hosting houses and businesses. Near the main gopuram (gateway tower) the businesses are focused on visitors to the temple with flower-sellers and other religious paraphernalia, but leave the main entrance street behind and you come to almost deserted streets where goats and cows make themselves comfortable and houses stand quiet waiting for residents to return home.

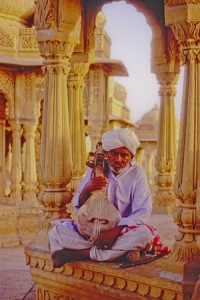

The gopuram are painted in many colors, but the temples beneath them aren’t. Instead, within the fourth gopuram there are ornately carved columned galleries that give relief from the sun. Everywhere are men and women who have made puja today, the men mostly clad in white dhoti (white sarongs folded up around their legs) with white streaks across their foreheads, the women in sari’s with red and yellow tikka between their eyes. There are families with children and beggars sleeping or selling flowers amongst the columns, but from the rooftops you can see across the gopuram to the rest of the city.

From Trichy, we caught another train and spent eight hours jouncing and bouncing our way back to Chennai, so I left the train with a backache. We abandoned our guide at the train station and headed out on our own to a hotel of our choice in a place called Poe’s Garden. I’m not sure where the area gets its name, but surely it can’t be related to Edgar Allan. The place is filled with pleasant houses and—gardens. Not a single pit or pendulum in sight. The traffic noise barely reaches the place where we’re staying and from our current roof top garden we can only see tree tops and water lilies and the pigeons that come to drink at the lily pool.

It’s a good thing, too. I’m tired. So is my travelling companion and this a pleasant place to slowly withdraw from the frenetic pace we’ve been living on this twenty-nine-day tour of southern India. Twenty years ago, I travelled in India for three months and fell in love with the country. After this trip, I’m far more ambivalent. I’m not sure why. Maybe it’s just the fatigue talking, or maybe it’s the fact that this was a tour that didn’t allow the freedom to travel the way I like to. As it was, I felt like I was watching a movie through a blindfold that would be stripped away for moments so that I could catch a glimpse of something marvellous, but never fully comprehend what I was seeing.

But then, perhaps that’s India. I don’t think it is possible to fully comprehend all its nuances.

Tonight, we catch a flight to Kuala Lumpur and on to Bali. Our first guesthouse is also supposed to be in a garden, this one with views of the ocean.

I’m sitting here on the train to Goa from Hampi. The train came from Calcutta and is already three hours late. That’s India. Nothing ever turns out as you expect.

Like the day before yesterday when at the end of the day we visited a hilltop temple that overlooks the Hampi ruins. Hampi is an ancient capital (early 1300s) that is actually mentioned in the epic Ramayana. By the 1600s it held over 500,000 people, but then it was sacked by a confederacy of rival sultanates. The ruins of the city remain today and are spread over 36 square kilometers around other-worldly mounds of boulders that seriously look as if they’re the remains of another, far older, civilization.

To see the sunset we went up beyond the temple’s rear gate where the light was turning pale gold and illuminating the heaps of boulders. We stayed there awhile with a family having a picnic. The light wind filled my face and the ubiquitous Indian haze softened the distance. Standing there, I felt like I could inhale the softness, especially after the music started playing in the temple. We headed back down to the temple and sat down to enjoy the peace. Then an orange-clad priest invited me up into the temple to take a seat and take part of the music. I don’t know quite what I was playing—small metal cups that you clap together in a syncopated rhythm. I was very bad at it, but I was still offered puja and a blessing. An unexpected welcome to Hampi.

On the other hand, yesterday I wanted to take photos of the sunrise over the Hampi ruins. Maybe it was my need to book end the visit—sunrise and sunset—so I was up at 5 am and had a driver arranged to take me to the ruins. We drove to Hampi and he dropped me at the stairs/trail that led up a very tall hill to the optimistically named ‘Sunrise Point’. The stairs were made of huge, uneven, pale slabs of stone that I could barely see through the darkness of pre-dawn. By the time I made it to the top of the stairs I was panting. Then I was faced by a conundrum—carry on, on a wide dusty path, or follow a sign that pointed off the main trail to Sunrise Point. Being Canadian, I followed the sign and found myself on a spider web of trails that led up and over boulders and through the brush. I found another set of stairs leading upward and headed up. And up. Over bounders. Up rough stairs. And up some more until I found a young French girl perched alone on a boulder like a messenger in a Dungeons and Dragons game. Above her was an even bigger boulder with vague indentations chipped into them as stairs.

She said she’d stopped where she was because she was afraid to go further, but more afraid of trying to get down. Looking at those half-formed stairs I totally got what she was saying and decided to stay there to photograph, if not the sunrise, at least the landscape as the sun turned it gold.

When the light changed, it seems that her assessment was correct. I headed down the rough stairs until I reached the place where I’d left the brush. Then I struck out on the path back towards my original stairs.

Only to have the path run out.

I retraced my footsteps and took another fork. It ended, too, and so did others so that eventually I had to make a decision: Go back to the second set of stairs if I could find them again (given the first set had mysteriously disappeared,) or get to the base of the mountain and hopefully find a path. I chose the latter and after much battling with cactus and thorn trees, bloodied, sweating and actually wondering what I would do if I fell and broke something, I found the bottom and a well-worn path next to a field of banana trees. That path eventually led me back into ruins where I enquired of a Japanese tour group what direction I should be going. I did find my way back, but I bear the thorn and cactus scars of my adventure.

So the lesson I’ve learned (actually, I should have remembered from my previous visit to this country) is that (for good or bad) in India nothing ever happens the way you expect.

Oh yes, and the train—we lost another three hours on our journey to Goa, arriving six hours late. I guess I should have expected it.

I’ve spent much of this blog writing about the great European mapmaking tradition and the exploration that went with it, but long before European Kings considered funding a certain wild venture to reach India and China by sailing west across the Atlantic, and long before Vasco de Gama sailed round the Cape of Africa and into the Indian Ocean, the Chinese were venturing westward, too. They sailed from Canton and through the Malay straight and into the Indian Ocean. They mapped it, too.

Chinese records indicate that trade between China and Africa began as early as the Han Dynasty (202 BC to AD 220). Two of Africa’s most powerful nations of the time, Kush and Axum had trade relationships through intermediaries. In Kush the remains of ancient pottery and bronze utensils indicate that they may have been copying the styles of the Chinese goods being brought to its ports by Arab traders. Axum may have been the source of the rhinoceros horn, ivory and tortoise shell that Roman traders took to China in AD166.

But this was trade by intermediary, not face to face trade. The first trade by Chinese with African is thought to have occurred not much later, but it probably didn’t occur on African shores. Accounts of ancient travelers indicate that in places like Ceylon merchants and sailors from as far afield as China, Persia, Homerite countries and Adulis (an African port city) came together to trade. One Chinese trader, Fa Xian, stayed in Ceylon for two years before returning home to write his accounts of the people he met.

During the time of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) records show that a Chinese did set foot on African soil. Du Huan, was a Chinese military officer who was captured by the Arabs during conflicts near Samarkand. After spending twelve years in the Abbasid Empire, he reappeared and wrote a record of his travels. Of the bits of that memoir that have been preserved over the ages, he speaks of travelling south over a great desert to the land of the black people, where there was little grain and no vegetation and malaria was endemic. Researchers today think this was probably modern-day Eritrea.

A Chinese junk from the 1270s was discovered in Guangzhou harbor in 1974 with cargo such as tortoiseshell, frankincense and ambergris that strongly suggest trade with Africa. Between 800 and 1400 Chinese goods were also making their way to Africa so that Chinese porcelain became common as decorations on houses and mosques and broken porcelain still apparently litters East African beaches. Chinese coins from the Tang Dynasty (the kind with the square hole in the middle) have been found along the coast and on islands like the Bajun and Zanzibar.

Of course, the Chinese travelers to these distant shores in these early days weren’t representatives of the Chinese dynasties. No they were merchants and traders. Most of these went as far as India and no farther and were content to trade with the middlemen who brought goods from Africa. But a few travelled further and the routes were known in the Kingdom of Heaven. In the ninth century the Tang Prime Minister and geographer, Jia Dan, knew of the sailing routes that gave 90 days from Canton to Arabia and 20 days for a further voyage southwest to a country called Sanlan.

Of course, if the Chinese were anything like the later Portuguese, this information could have come from Arab sailors as a result of the government confiscating all maps from visiting sailors, but a map compiled between 1311 and 1320 by the Chinese cartographer Zhu Siben clearly shows the triangular southwest pointing African continent at a time when the western world thought that Africa didn’t end, but instead the landmass continued on eastward before joining the mainland again and enclosing the Indian Ocean as a great inland sea.

Just think of what this map suggests: The Chinese were there first. If they had kept going, they could have discovered Europe long before the Europeans ‘discovered’ the route to China.

The ancient T.O. maps didn’t represent reality, but they did map the reality of the Christian spirit at the time. Portolan Charts gave a realistic representation of coastlines and the work of the Indian spy/cartographers, placed rivers on the maps well before aerial mapping existed.

One of the last bastions of ‘unmapped’ territory was the Amazon basin of Brazil. In 1799 Alexander von Humboldt, the son of a Prussian baron, spent five years travelling from Venezuela’s Orinoco river through the Amazon, collecting specimens and surveying. Afterwards he produced 33 volumes of maps and illustrations. That was the last mapping for over a hundred and fifty years except for the occasional scientific or rubber company exploration.

Until 1970.

That’s when the Brazilian government got the idea to construct a highway from the Atlantic Coast, across 5,000 kilometers (about 3,400 miles) of rainforest to the Peruvian border. The construction was a nightmare due to a dearth of maps. The rainforest had too many clouds and—gee, rain in a rainforest?—for aerial mapping to work. The result was construction following ground-based surveyors who were barely ahead of the bulldozers and this led to the construction having to cross the same river multiple times leading to enormous unforeseen costs.

Enter the cartographers. In this case it was cartographers and the invention of side-looking radar (SLAR). SLAR is an improvement on the radar that helped safe Great Britain during the Battle of Britain. It’s the invention that allows radar to be shot out the side of an aircraft to take long horizontal pictures of the landscape. This technology can ‘see’ through clouds and trees to the landforms. With the help of computers, SLAR can provide accurate pictures of the rise and fall of the landscape.

The survey team with their aircraft arrived in Brazil on the summer of 1971. In just under a year SLAR mapped the Amazon in 32-kilometer-wide swaths which lead to the first detailed maps of the Amazon and an understanding that this huge territory wasn’t the previously-thought Amazon “basin”. Instead they found that only about 20% of the area was lowlands, with most of the landscape being hilly and mountainous.

This ‘sped up’ the construction of the highway which was completed in 2011 except for a single bridge in the Peruvian part of the road. But what has this meant for the area? For some, it replaces weeks of travel on dirt roads to a relatively short drive. For others it promises income from a potential huge influx of tourists. But what it also means is environmental degradation.

Brazil has a long history of environmental issues springing directly from road-building into this relatively delicate biosphere. Previous road building shows that almost 90% of deforestation lies within 50 kilometers of a road (about 23miles). Timber and mineral extraction are followed by hydroelectric dam development and the destruction this causes.

What’s disturbing is that the Amazon is truly the lungs of the world and cartography has provided the data needed to seriously damage those lungs. It places a different perspective on maps; one that undermines the beauty of what I’ve always thought and suggests the need for ethical standards that stand up to the push of corporate greed.

There are means to ameliorate the potential destructiveness of developments like the Transoceanic Highway or the construction of pipelines like the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline through British Columbia, but it requires people like cartographers, citizens, and government officials to demand agreements that protect the environment BEFORE, planning starts. Otherwise ‘progress’ can just as easily lead to widespread destruction like what is happening in the Amazon.

The new maps of the Amazon not only map progress, but also the destruction of a reality. Unlike the T.O. maps of the Christians that cemented the Christian spirit firmly in Jerusalem, these maps not only mark destruction of biodiversity, but they record the destruction of the spirit of the indigenous people.

As I said way back when I started blogging about maps, some of my favorite early memories are of looking at maps with my family as we started out on some adventure, or as I fantasized about places around the world that I wanted to see. I guess that experience made me a map fan. In reaction to my blog about whether maps should be in books, a few blog readers reminded me that they also like to read maps and in particular find satisfaction in maps contained in books because those maps offer the opportunity to better understand the relationship and distances between places written about in the book. The readers enjoyed following along with the characters as they moved across the landscape.

This enjoyment with following voyages isn’t limited to readers. I recently lost an afternoon playing with the Facebook Cities I’ve Visited app. I think Facebook and Tripadvisor are on to something there – the need to record and understand just where we’ve been in relation to where we are right now.

I mentioned previously that I always carry a map when I travel and mark my journey down for my future enjoyment. As a writer, taken in conjunction with my journals, these maps always help me remember the places I’ve been or travelled through and provide a cartographic representation of terrain that my aging brain cells might have forgotten. But maps aren’t just used by me during my journeys. My family always hauls out the atlas and follows along as I wander. On my last trip, to Peru, a network of writer friends around North America followed along as I did sent in my blogs like an itinerant reporter. I suppose the satisfaction for them, was not only that they could follow along, but that they could also get a sense of the relationship of where I was to their location.

Because although maps represent a greater world, they are also are very egocentric creations. By this I mean that maps are drawn by the creator not necessarily to draw reality, but to draw their reality. Case in point is a lovely 1886 Imperial Federation Map if the World Showing the Extent of the British Empire which shows Britain at the centre of the map (much as the medieval T/O maps showed Jerusalem at the centre of the known world). The wonderful map uses the Meracator projection which nicely enlarges landmasses in the northern hemisphere (including Britain) and also includes mythic Atlas holding aloft the world which is straddled by lithesome Britannia who is surrounded and adored by the lesser ‘races’ (read colonies), all peering up at Britannia’s greatness. Not simply a map it seems, but also a satisfying cartographic representation of the way Brits at that time wanted to view the world and themselves.

To some degree I think the Cities I’ve Visited acts something like the 1886 map: although we aren’t placing ourselves above the world, it gives us comfort with our place in the world. We create our representation of the places we’ve touched and maybe that gives them more reality for us. Perhaps that satisfaction also includes a little reassurance of our place in the world?

So when I was done with Cities I’ve Visited, I was very satisfied that I’d trod so many places in the world, but also fairly embarrassed. I felt almost like I was competing with some cyber-other to show that my vision of the world was broader because I’d been more places. Was it really a competition? The App said the average person has visited 17 cities. I was at 247 and I stopped when I started to feel really stupid (not to mention that I’d wasted a good chunk of the afternoon).

The whole experience reminded me of too many tourists I’ve laughed over who arrive at a place, leap out of the tour bus, take a photo and then leave to drive like mad to the next place and the next photo. That phenomena always put me in mind of a mission to collect places like notches on a belt – or like a dog leaving photographic spoor like doggie–do reminders of where they’ve been.

It makes me wonder if our egocentric need for maps is something like our need to collect, buy and own – as a means to quell our unquenchable need for satisfaction.

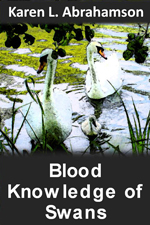

Two new short stories are now available on Amazon.com and Smashwords.

A small child, a string of pearls and a colony of swans converge in this short story of family life gone wrong. In Bella’s world of beautiful swans, her mother is the most beautiful creature of all. But swans abandon Bella every year and now her mother may abandon her, too. In a world filled with magic, what’s a child to do?

A small child, a string of pearls and a colony of swans converge in this short story of family life gone wrong. In Bella’s world of beautiful swans, her mother is the most beautiful creature of all. But swans abandon Bella every year and now her mother may abandon her, too. In a world filled with magic, what’s a child to do?

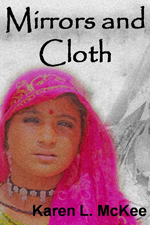

Lost in Rajasthan, the home of camels, hevalis, ornate men’s turbans and women draped in mirror-embossed saris, freelance journalist, Lena, must deal with strange customs and two men who profess to love her. Choosing the right path can be as convoluted as the twists on a Rajasthani turban.

Lost in Rajasthan, the home of camels, hevalis, ornate men’s turbans and women draped in mirror-embossed saris, freelance journalist, Lena, must deal with strange customs and two men who profess to love her. Choosing the right path can be as convoluted as the twists on a Rajasthani turban.

So I’m on the final countdown. Eleven days from now I’ll be on a plane heading towards Lima, Peru, on my virgin trip to South America. In between trying to get books finished and manage my business, I’ve been trying to pack and get my equipment in order. I’ve cleaned and packed my camera equipment. I’ve bought a lightweight computer. I’ve made plans to blog and I have my smart phone so I can keep in touch. I even have my kindle so I don’t have to carry a plethora of books.

There’s only one problem. I feel sick about it.

All this stuff weighs a ton. There are electrical cords and plug adapters and more plugs and batteries until I wonder whether I’m going trekking or to the office. I keep telling myself all this stuff will help my travel, but I guess I’ll reserve judgment until I hike my pack onto my back. Let me tell you about the changes the electronic age has made.

1. I don’t have to carry film. Instead I have a little external hard drive and numerous memory cards. This might not seem like such a big deal, but fifty to seventy-five rolls of high quality slide film are far heavier than you think, especially when you have to carry them on your back. Not only do they weigh a lot, they also take up a huge amount of space and time. I recall going through a SeaTac Security counter where they wanted to open and check each roll of film after I refused to let them put it through the x-ray. I had the time, so I stood there and let them do it, until they finally gave up. Seventy-five rolls is that much. Shooting digital on my last trip I shot over 3000 frames—the equivalent of about 86 rolls.

It’s interesting as I pack now. I’m using the large pack I took to India for three months and although this time I’m packing the same amount of clothes AND a sleeping bag, the pack is still almost empty compared to the old trip because of the lack of film. Which means a lighter pack and more room for the souvenirs and gifts I inevitably bring home.

2. Think books. There’s a guidebook to Peru that I’ll still carry, though I have it on Kindle also. (I always have a backpacker’s guide like Rough Guide or Lonely Planet). Right there, you have a heavy tome. Then any books you might want to read over a month or so away and you have a few more pounds. So this time I have my kindle loaded up with far more books than I know I’ll get a chance to read, but better to have too many than not enough. One of my most horrendous memories is of being caught in Burma with only the Thornbirds to read. Twice. I still shudder.

3. The telephone. Before cell phones took over the world I’ve had to waste a day wandering around to find a pay phone, stand in line and then make connections from whatever backwater I happen to be in. Having the smart phone will help out with e-mail and keeping in touch, so though it’s an additional weight I think it’s a weight that will save me in time. On the other hand it’s going to keep me more connected and that isn’t always a good thing when I’m trying to focus on the place I’m in.

4. The computer. Let me just say I always journal when I travel. It’s the best way I know of to record the events, the feel and emotion of a place. Often I’ll write myself to sleep and wake up the next morning and write more before I go off on the day’s new adventures. Having the computer presumably means I can do this electronically, but I’m not sure if I will, even if I need it to blog. I have always carried coiled notebooks. A notebook can’t break down and can be salvaged if it falls in a river. A notebook is less attractive to steal and a pen or pencil still feels more real in my hand when I travel. However I have to say that after filling four or five notebooks on my India trip, there may be room for computers though I feel both more vulnerable and excited to try this out.

So for this trip to a new continent, I’m trying a new form of travel: One that’s a little lighter and that comes with a whole lot more (electrical) connections.

If I don’t get hit over the head by someone trying to steal it.

Or fall in a river.

Okay, so I’m going to Peru. I’m going to follow the Gringo Loop and hike the Inca Trail all the way to Machu Picchu.

Or at least that’s the plan. If food poisoning and altitude sickness don’t get me first.

But then neither of them has ever stopped me before. You see, I like to travel. I like to travel just as much as I like to write fiction and so I thought I’d combine my two passions in a blog as I get ready for the trip and as I hike (uphill both ways) to Machu Picchu.

A lot of people ask me how I decide where I want to go. Yes, I’ve been to ‘normal places’ in Europe, but mostly I travel a bit off the beaten path. I’ve traveled through East and West Africa by truck. I’ve spent three months in northern India travelling by train, bus, jeep and, dare I say, camel. I spent two months travelling the Silk Road through China and made side journeys to the Tibetan highlands. I’ve travelled in Egypt, Burma, and Cambodia and lived in Thailand. A good friend described my travel as going to all the weird places in the world. Of course he followed it up with the question “Why don’t you go someplace normal? Like Palm Springs? Like Florida?”

Answering that question is a lot like answering a best-selling author who, when I told her I was writing a suspense novel with romantic overtones set in Afghanistan, asked to me why in god’s name I would write something like that.

The answer?

Why not?

Besides, it was something I was interested in. It was something far away and foreign that I wanted to understand. That inspiration became Ashes and Light, it was just after the invasion of Afghanistan and I wanted to understand what was happening in that country. I’d enjoyed Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, but I wanted to write something that was more mainstream, that would reach into the hearts of readers who wouldn’t read The Kite Runner and provide them with insights that might explain – even a little bit – the misunderstandings that were brewing between Islam and the rest of the world. My travels to northwest India and far western China—areas that enjoy similarities of people, religion, culture and landscape with Afghanistan—all helped me with the book.

While the Afghan story arose from a cerebral process, sometimes the idea for a story or destination arises from something far simpler. Sometimes it’s another traveler’s tale. Sometimes it’s a photo. In the case of Peru, it was two postcards: One was a framed postcard in my doctor’s office of a traditionally dressed Peruvian girl peeking out from behind a brightly striped blanket. There was something so fresh and lovely in her face that it made me want to meet people like her. The other post card was of Machu Picchu and was from my parents who were on a world cruise. Unfortunately, they couldn’t visit the ancient Inca site because they are 83 years old and if the altitude sickness didn’t get them, the uneven ground would have.

So part of my reason for going to Peru is to bring the feel of Peru back to my folks. And that’s what I see travel as being—one part inspiration, one part imagination, and a whole lot of hard work and a magnificent gift—when it works. A lot like writing a book.

So I leave for Peru on March 25, 2011. Come on along, if you like, and I’ll try to get us through without the food poisoning and altitude sickness.