Bhutan: Preparing for the Perilous Landscape

Since returning home and while suffering from jet lag I’ve had a number of people ask me where I was travelling. When I answer “Bhutan” I’ve had a lot of blank stares, so just to clarify, Bhutan is a small Himalayan country pressed, geographically, between Tibetan China and India. In fact, both larger countries have, in the past, taken over parts of Bhutan, with the most recent encroachment being the Chinese moving into and claiming Bhutanese highlands. The Chinese were presumably driven by the need to claim more of the very rare and very valuable Bhutanese cordyceps—a fungus that grows out of a high-altitude caterpillar’s forehead that “purportedly has medicinal powers matched only by rhino horns, elephant tusks and tiger penises” (according to my Lonely Planet guide.)

So, Bhutan whose symbol is the thunder dragon and which enjoys a Tibetan style culture that is purely its own, sits partially in very high mountains and partially in lovely valley floors. The lowest of those valleys is apparently still higher than some of the lowest elevation cities in Peru—the last country that I visited where altitude was involved. Given how altitude sickness struck me in Peru (I couldn’t take the preventative drugs because I was technically allergic to it), I was more than a little paranoid about visiting Bhutan. The skull-shattering headaches I had in Peru made me think I might understand how the caterpillar felt when being attacked by the head fungus. So, in preparation for Bhutan, I decided to go through my own ordeal before I left on the trip. I decided to get tested to see if I really was allergic.

The altitude sickness drug is called Diamox and it is a sulfa-based drug, to which I am allergic (according to doctors that I saw when I was sixteen years old). In the interest of seeing whether my body chemistry had changed, my current family doctor referred me to an allergist—a referral that took three months before I had an appointment, putting me only one month from my Bhutanese departure date. I arrived at the appointment and the allergist took my blood pressure, checked my heart etc., told me that I was healthy (which I knew) and then advised that there were NO tests for sulfa allergies, but if I’d like to go into the hospital for three days they could possibly test me for Penicillin allergies. (I mean what the****?) He suggested that I not take the Diamox but, as an afterthought, suggested that I might want to call the local travel clinic for a second opinion.

Given my experience in Peru and my determination to go to Bhutan, that was exactly what I did. I spoke to the travel doctor who listened to my issue. She told me to take the Diamox—there was, apparently, no cross-reactivity (whatever that means). So I did that, too.

In Bhutan I travelled over passes that were 3,900 meters high and spent days at 3,300 meters—considerably higher than where I became sick in Peru (though at 3,300 meters I had frequent headaches even with the Diamox), but it was worth it. I even climbed a mountain to the Tiger’s Nest monastery at an altitude of about 3,000 meters and am here to tell the tale.

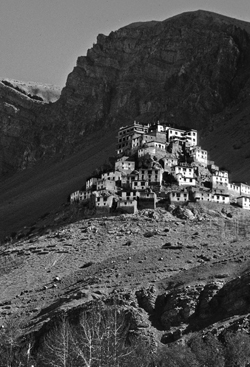

So the perilous Bhutanese landscape was really simply the magical landscape of the thunder dragon, Himalayan mountain peaks, picturesque plateaus and river valley’s so deep they looked bottomless. Everywhere there were towering cypress trees on the heights and rhododendron trees lower down. Rice fields heavy and ready to harvest lay along the valley bottoms and on stepped paddies up the valley sides. Dotting this landscape were the small towns and cities and the huge white-walled monastic fortresses called dzongs.

Most memorable of all were the beams of God-light shining through the clouds to spotlight white-washed temples or green fields. It was—supernatural, superlative, spectacular, breathtaking. And I was able to enjoy it all, thanks to the Diamox.

I pity the poor caterpillar who can’t enjoy the rarified heights where it lives.