They Came From the Rising Sun

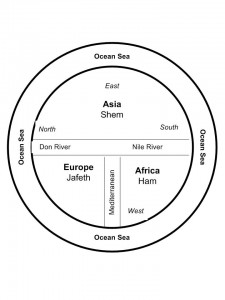

I’ve spent much of this blog writing about the great European mapmaking tradition and the exploration that went with it, but long before European Kings considered funding a certain wild venture to reach India and China by sailing west across the Atlantic, and long before Vasco de Gama sailed round the Cape of Africa and into the Indian Ocean, the Chinese were venturing westward, too. They sailed from Canton and through the Malay straight and into the Indian Ocean. They mapped it, too.

Chinese records indicate that trade between China and Africa began as early as the Han Dynasty (202 BC to AD 220). Two of Africa’s most powerful nations of the time, Kush and Axum had trade relationships through intermediaries. In Kush the remains of ancient pottery and bronze utensils indicate that they may have been copying the styles of the Chinese goods being brought to its ports by Arab traders. Axum may have been the source of the rhinoceros horn, ivory and tortoise shell that Roman traders took to China in AD166.

But this was trade by intermediary, not face to face trade. The first trade by Chinese with African is thought to have occurred not much later, but it probably didn’t occur on African shores. Accounts of ancient travelers indicate that in places like Ceylon merchants and sailors from as far afield as China, Persia, Homerite countries and Adulis (an African port city) came together to trade. One Chinese trader, Fa Xian, stayed in Ceylon for two years before returning home to write his accounts of the people he met.

During the time of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) records show that a Chinese did set foot on African soil. Du Huan, was a Chinese military officer who was captured by the Arabs during conflicts near Samarkand. After spending twelve years in the Abbasid Empire, he reappeared and wrote a record of his travels. Of the bits of that memoir that have been preserved over the ages, he speaks of travelling south over a great desert to the land of the black people, where there was little grain and no vegetation and malaria was endemic. Researchers today think this was probably modern-day Eritrea.

A Chinese junk from the 1270s was discovered in Guangzhou harbor in 1974 with cargo such as tortoiseshell, frankincense and ambergris that strongly suggest trade with Africa. Between 800 and 1400 Chinese goods were also making their way to Africa so that Chinese porcelain became common as decorations on houses and mosques and broken porcelain still apparently litters East African beaches. Chinese coins from the Tang Dynasty (the kind with the square hole in the middle) have been found along the coast and on islands like the Bajun and Zanzibar.

Of course, the Chinese travelers to these distant shores in these early days weren’t representatives of the Chinese dynasties. No they were merchants and traders. Most of these went as far as India and no farther and were content to trade with the middlemen who brought goods from Africa. But a few travelled further and the routes were known in the Kingdom of Heaven. In the ninth century the Tang Prime Minister and geographer, Jia Dan, knew of the sailing routes that gave 90 days from Canton to Arabia and 20 days for a further voyage southwest to a country called Sanlan.

Of course, if the Chinese were anything like the later Portuguese, this information could have come from Arab sailors as a result of the government confiscating all maps from visiting sailors, but a map compiled between 1311 and 1320 by the Chinese cartographer Zhu Siben clearly shows the triangular southwest pointing African continent at a time when the western world thought that Africa didn’t end, but instead the landmass continued on eastward before joining the mainland again and enclosing the Indian Ocean as a great inland sea.

Just think of what this map suggests: The Chinese were there first. If they had kept going, they could have discovered Europe long before the Europeans ‘discovered’ the route to China.