Free Fiction

The second to last installment of Mutable Things is up today. Chapter 25 and 26 are Here.

The second to last installment of Mutable Things is up today. Chapter 25 and 26 are Here.

Free Fiction

Chapters 23 and 24 of Mutable Things are now available here.

Chapters 23 and 24 of Mutable Things are now available here.

Spy Lands –Who really discovered the coasts of America

I mentioned last week about spies and maps and government subterfuge as aspects of maps that we rarely think about. Municipal governments still fool residents with streets on maps that are planned, but haven’t been built. Map makers take liberties with place names and add imaginary towns and streets that reflect their biases for and against university football teams. But in the past spies were frequently involved in cartographic subterfuge.

For instance, most of us were schooled that Captain Cook was the first European to lay eyes on the north western coast of North America. However there is mounting evidence that the English privateer (government sanctioned pirate) Sir Francis Drake, not Cook, first saw the coast of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia between 1577 and 1580 – 160 years before Cook’s journey.

Why isn’t this known?

First of all because some historians are hard pressed to let go of old ideas, but second of all because Drake’s journey was likely suppressed and evidence of it hidden, because of disputes with the Spanish that were, later, going to erupt into war. Drake is confirmed to have travelled as far north as Mendocino, California, the farthest north the Spanish had been, but a 412 year old map commemorating Drakes circumnavigation of the globe shows details of the coast of British Columbia that no one could have known unless they had been there. Additionally, archeological evidence – 1571 British coins and equipment – have been found in Oregon and Victoria, B.C. gardens, so that Drake is believed to have travelled as far north as Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. Finally, Drake’s cousin confessed under torture to the Spanish, that a fabled North Pacific island, Nova Albion, had been discovered by Drake and claimed for England 29 years before Samuel Champlain founded Quebec and before there was a Virginia on any map. This is believed to have been Vancouver Island, kept secret.

A further example of cartographic spies, deals with those icons, Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. Columbus, we’re taught, discovered the Americas while looking for China. Cabot’s fame is due to his first North American landfall by a European. Or at least that’s what we’re taught. But in a 1498 letter that was penned just months after Cabot’s historic return from Newfoundland, a spy in England wrote to Columbus and talked about earlier voyages by men from Bristol to the same place Cabot had been and that these earlier voyages had been to an “Island of Brasil” and that Cabot’s landfall “is believed to be the mainland that the men from Bristol found”. The spy’s letter also mentions that these voyages from Bristol were well known to Columbus – something that is further supported because Columbus had spent time in Bristol and Iceland in the 1470s – almost 20 years before he managed to convince the Spanish monarchy to fund his explorations. Did Columbus use this knowledge to convince Isabella? Did he use it to calm his crew on his long crossing?

A further example of cartographic spies, deals with those icons, Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. Columbus, we’re taught, discovered the Americas while looking for China. Cabot’s fame is due to his first North American landfall by a European. Or at least that’s what we’re taught. But in a 1498 letter that was penned just months after Cabot’s historic return from Newfoundland, a spy in England wrote to Columbus and talked about earlier voyages by men from Bristol to the same place Cabot had been and that these earlier voyages had been to an “Island of Brasil” and that Cabot’s landfall “is believed to be the mainland that the men from Bristol found”. The spy’s letter also mentions that these voyages from Bristol were well known to Columbus – something that is further supported because Columbus had spent time in Bristol and Iceland in the 1470s – almost 20 years before he managed to convince the Spanish monarchy to fund his explorations. Did Columbus use this knowledge to convince Isabella? Did he use it to calm his crew on his long crossing?

We may never know, and even if we do, will it matter? For Columbus IS an icon that history won’t forget, but what this shows is how secrets and spies permeate the European history of maps, so that who really ‘discovered’ the coasts of America may never be known. Of course, just talk to a First Nations/Native American person and they’ll tell you we’ve got it all wrong anyway. North America had been ‘discovered’ long before any European left home.

We may never know, and even if we do, will it matter? For Columbus IS an icon that history won’t forget, but what this shows is how secrets and spies permeate the European history of maps, so that who really ‘discovered’ the coasts of America may never be known. Of course, just talk to a First Nations/Native American person and they’ll tell you we’ve got it all wrong anyway. North America had been ‘discovered’ long before any European left home.

Free Fiction

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

Free Fiction

Free Fiction brings bleak times for Jaymee and David. Chapters 19 and 20 are up here.

Free Fiction brings bleak times for Jaymee and David. Chapters 19 and 20 are up here.

The Roots of the World

For men like Fra Mauro (see last post), the exploration of the external world led to an understanding of the inner landscape of men. So too, from the triangulation of the world (see post here) came a greater understanding of the internal shape of the earth.

I mentioned previously that in order to determine the shape of the world, a French survey team went to Ecuador and Peru at the same time as a team went to Lapland. Unfortunately for the Peruvian team, the Lapland team discovered the answer to the scientific question long before the Peruvian team ever finished their survey. While in South America, however, the Peruvian team struggled over mountains and through jungles and noted different gravity readings as they took their survey measurements along their route. They surmised that the differences in the readings might reflect the varying landscape and theorized that mountains might be made of less dense material than the lowlands. A good theory, but it took over a hundred years for the matter to be more fully explored and the discovery was made far from South America. It took the British Raj’s need to survey India to bring understanding to what the mass of mountains might mean.

In the mid nineteenth century, the horrendous task of surveying India through triangulation was almost undone by the discovery of an error of some 150 meters between the distance the triangulation measurements computed, and an actual direct surface measurement. To determine what had led to the error, the cartographers involved had to reexamine their assumptions – in this case they had assumed that the mass of the Himalayan Mountains would greatly influence the gravity measurements of their survey instruments. What they found was that they had overestimated the lower mass of the mountains.

This led to a theory of the earth’s crust that still exists today, namely that every (theoretical) column of the earth (from core to outer surface following a theoretical plum line) should have approximately the same mass. Given that tall mountains have a lower mass, they must have an equally large (but low mass) protuberance at the bottom of the earth’s crust to achieve the same mass as denser areas of the earth’s crust. Conversely, under the oceans where the ocean basins are very dense, the earth’s crust would be relatively thin. The theoretical result would be that inside the earth there would be a mirroring of the plains, mountains and ocean valleys we see on the surface, much like a tall iceberg has a large underwater presence to balance it out. Modern science has supported this, by obtaining crust measurements off the coast of South America that show the Andes have roots as deep as 75 kilometers.

Think of this the next time you are crossing the mountains, staring up at those tall, snow-covered peaks, for they are the frosting, the outer conceit of an iceberg of stone that conceals the deeper reality of the roots of the mountains.

Much like Fra Mauro saw the illusions of men obscure the truth of his map of the world.

Free Fiction — and apologies

I want to apologize for missing last week’s posting of new chapters in Jaymee and David’s story, but a family emergency kept me away from the right material on my computer, I hope this week’s installment keeps you reading. Click here to read chapter 17 and 18.

I want to apologize for missing last week’s posting of new chapters in Jaymee and David’s story, but a family emergency kept me away from the right material on my computer, I hope this week’s installment keeps you reading. Click here to read chapter 17 and 18.

Free Fiction Wednesday

The story continues for Jaymee and David Corbin, and of course things get worse. To read on, click HERE.

The story continues for Jaymee and David Corbin, and of course things get worse. To read on, click HERE.

The World Has Three Points

I mentioned last week how the ancient Egyptian, Eratosthrenes, used a column and a shadow as two sides of a triangle to estimate the size of the earth, which shows the importance of geometry to cartography. Nowhere was this more evident than in mapping the earth, where triangulation, (the process of determining the location of a point by measuring angles to an unknown point from known points at either end of a fixed baseline), was literally used to measure the location of everything in relation to everything else.

I mentioned last week how the ancient Egyptian, Eratosthrenes, used a column and a shadow as two sides of a triangle to estimate the size of the earth, which shows the importance of geometry to cartography. Nowhere was this more evident than in mapping the earth, where triangulation, (the process of determining the location of a point by measuring angles to an unknown point from known points at either end of a fixed baseline), was literally used to measure the location of everything in relation to everything else.

Geometry and triangulation had actually proven themselves previous to Eratosthrenes. They’d been used to measure the heights of the pyramids and had also had been highlighted by the ancient Chinese as an important principle of mapmaking. Unfortunately this wasn’t well known in Europe even though the Arabic influence brought such surveying methods into old Spain. Instead, Europe was still transcribing tourist tales and fanciful stories onto paper and selling these for parlor display based on their beautiful illuminations, rather than spending their time surveying the landscape.

Apparently the first European to get serious about the use of triangulation was a Dutchman named Gemma Frisius who suggested using triangulation as a means to pinpoint the location of places on maps. The technique gradually spread through the 1500s, but it wasn’t until the 1600s that Europe got serious. A Dutchman named Snell began the process of surveying the landscape with a chained line of triangles (much like the triangles the American flag is folded into)across the countryside for a distance of 70 miles. The use of Snell’s process led to a rise in the quality of the Dutch maps and, in comparison, the decline of French maps into dependence upon engraving and elegant color as their selling feature – all well and good as a parlor adornment, but not what you want if you actually want to do something with the map you made.

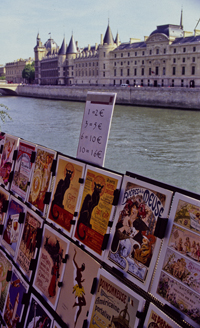

Enter Guillaume Deslisle: In the late 1600s this young Frenchman began to change maps from things of the arts to matters of science. At a time when the great rulers such as Louis XIV knew little about the countries they ruled, he began to use triangulation surveys to permanently shift and fix continents and islands on the map, and even settled the age-old argument about the length of the Mediterranean Sea (41 degrees). The work of Deslisle and his kin led to the first mapping of Russia, or Muscovia as it was known at the time, and eventually influenced the French Minister for Home Affairs and advisor to Louis the XIV, Jean Colbert, to push for the mapping of France.

Enter Guillaume Deslisle: In the late 1600s this young Frenchman began to change maps from things of the arts to matters of science. At a time when the great rulers such as Louis XIV knew little about the countries they ruled, he began to use triangulation surveys to permanently shift and fix continents and islands on the map, and even settled the age-old argument about the length of the Mediterranean Sea (41 degrees). The work of Deslisle and his kin led to the first mapping of Russia, or Muscovia as it was known at the time, and eventually influenced the French Minister for Home Affairs and advisor to Louis the XIV, Jean Colbert, to push for the mapping of France.

In 1663, Colbert ordered that each French province’s maps be examined to see if they were of sufficient quality. If they were not, qualified surveys were to be undertaken. This eventually led to Abbe Jean Picard overseeing the first precisely measured chain of triangles and topographical surveys around Paris – the two preliminary foundations to accurate mapping. The extension of this process led to France being mapped and became the standard practice for scientific mapmakers. It was used in the cartographic expeditions used in Lapland and Peru discussed in my last cartographic blog, in mapping the Himalayas, the English countryside and, the Grand Canyon and everywhere else in the world.

In 1663, Colbert ordered that each French province’s maps be examined to see if they were of sufficient quality. If they were not, qualified surveys were to be undertaken. This eventually led to Abbe Jean Picard overseeing the first precisely measured chain of triangles and topographical surveys around Paris – the two preliminary foundations to accurate mapping. The extension of this process led to France being mapped and became the standard practice for scientific mapmakers. It was used in the cartographic expeditions used in Lapland and Peru discussed in my last cartographic blog, in mapping the Himalayas, the English countryside and, the Grand Canyon and everywhere else in the world.

But the work of Deslisle and Picard had unforeseen impacts. Like the magic in my books, the new maps seriously revised France’s boundaries and coastal outline. The world’s shape was changed again – all because of three points.

But the work of Deslisle and Picard had unforeseen impacts. Like the magic in my books, the new maps seriously revised France’s boundaries and coastal outline. The world’s shape was changed again – all because of three points.