Great Expectations: Cats and Readers

This past week I was supposed to be on the coast of Oregon with a group of writers learning about marketing books to bookstores. I was really looking forward to the trip and being with a group of great friends. I had everything packed and ready to be loaded into my car. My cats were primed and ready to for the trip. (They always travel with me, and the hotel where I stay at has known these boys since they were babies—it’s like a second home).

Then Ben, the larger of the two boys got sick and not just throwing up, but a total shut down. He quit eating (a VERY big thing for this guy) and drinking and became very quiet and cooperative. Now you have to know Ben. This is a cat that pulls paintings off walls and statues off shelves just to get your attention. When he took a downturn I ended up taking him to the emergency veterinarian. The next day more vets and more bills and at that point the I was still holding up hope that he might recover and I might still head to my course a day late.

Not to be.

More tests, more bills and by this point I was administering subcutaneous fluids twice a day, force feeding three times and day and wrestling pills down his throat twice a day. It’s a wonder he’s still speaking to me. How do you spell stress?

The point I’m making here is that all my expectations were dashed and so I had to totally regroup and refocus myself from a week that I had booked off from work to a week working and caring for sick cats (yes, Ben’s brother got the same bug). It was jarring. It was unpleasant not least because I had a sick cat, but also because I wasn’t doing what my mind had expected. I raise this because it brought home something important writers need to think about, which is reader expectation.

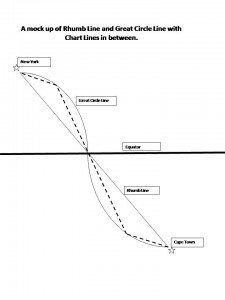

Reader expectation is what the reader is expecting to experience in a book. For instance, if J.R.R. Tolkien had written a shoot-‘em-up Science Fiction book as a follow-up to the Lord of the Rings, think about how disappointed the Lord of the Rings fan would have been when they bought the book. Same goes for the reader who picks up a book that has a cover and blurb that looks like a suspense story, but when they get reading they find it’s women’s fiction. Or the reader whose book spends an immense amount of time early on lovingly describing the gun the hero owns, but by the end of the book the gun has never been used or even appeared in the story again. Each of these authors has violated reader expectations.

A few days ago I was talking with a writer friend of mine. He was bummed out because his editor at a New York publisher had turned down book two of his two book contract and my friend couldn’t understand what that had happened. In discussion with the writer he advised that book one was a lavish fantasy involving the Jewish kabala. Book two was a comedic superhero novel. Anyone see a problem here? Apparently his editor did, because the publishing house had ‘bought’ my friend as an author of lavish Jewish fantasies, but his second novel failed to deliver this in every respect. The publishing house likely turned the book down out of concern for reader expectations. Basically my writer friend was asking to his readers to give up the expectations he had created through his first book and start all over again. I suggest that readers don’t like to do this anymore than I wanted to give up my week in Oregon.

In all of these cases the author failed to meet reader expectations and as a result the reader would have as dissatisfying an experience as I have had this week. Yes, the book(s) may still have been well written. My writer friends second book was undoubtedly wonderful (he’s a great writer), but it wasn’t what the publisher was banking on the reader wanting. He should have written another Jewish fantasy. He should have written under a different name for the superhero novel. Not that all our books have to be the same, but if we want to establish a career as a writer, we need to establish a brand. We might have several brands for different kinds of books written under different names. For instance my romance novels are under Karen L. McKee, while my fantasy/SF is written under Karen L. Abrahamson. It helps reader know what they are getting and this helps meet reader expectation.

So as writers we need to make sure that we don’t put our readers through the experience I’ve had this week. With two sick cats, I definitely didn’t get what I’d thought I bought when I booked the week off.

(and in case you were interested, the boys are both on the mend.