The inimitable Joanna Vandervlugt interviewed me about Beneath Malabar Nets

Check out the Podcast HERE.

Check out the Podcast HERE.

Sometimes… sometimes this world can be so darned hard to be in—like reading about the death of the last male northern white rhino, or that 18 of the Tigers ‘rescued’ from a Thai temple ended up dying. And then there’s the whole darn political situation where nobody seems to speak the whole truth.

But other times the world can be such a giving place that it overwhelms. That was my experience in Bhutan.

As I mentioned in a prior post, Bhutan is a Buddhist country. It isn’t a big country. It isn’t particularly modern in the way places like London, New York, or even Bangkok might be, but it’s a country that seems to understand the concept of ‘enough’. It might not be a wealthy country (up until this year it’s biggest source of revenue was tourism), but the government has decided not to rate the well-being of the country not on gross domestic product (in other words, how much does the country produce or earn each year), but instead they assess the country on Gross Domestic Happiness.

I’m not quite sure how they measure this apparently quite ‘ephemeral’ concept, but I have to say that the country seems to be doing quite well. Some of it seems to be the personal realizations of the citizens that they can have ‘enough’—maybe not from driving for the ‘high life’, but from something else. For instance, the country has put a lot of energy into education and has a well-educated middle class. This has lead to many young people leaving their traditional country villages for the city leading to pressure on Thimpu and Paro (the two main cities) and some concern for the farming tradition of the country. What did the country do? It offered sizeable subsidies for the well-educated young people to return to farming—and its working!

Bhutan is also a country that is trying hard to balance growth with protection of the environment. Compared to most countries around the world, Bhutan has actually seen an increase in the its national forest cover and it does things like set aside an entire fertile valley floor in order to preserve the habitat of the rare black-necked crane. Pretty progressive.

At the same time, tradition is everywhere. Come to a bridge, a river confluence, or mountain pass, and you find yourself amongst the fluttering host of red, yellow, green, blue or white prayer flags. Tradition says that with every gust of wind, the prayers connected to the flags are sent skyward to the benefit of the prayer flag’s patron. You become a patron by deciding to put up the flags but you’ll also see clusters of white prayer flags on poles that are raised in remembrance of the newly dead.

While I was in Thimpu, the capital, I had the chance to visit a Bhutanese astrologer who informed me that:

Given the astrologer was exactly right about the couple of bad years, I took the prayer flags he recommended and thought that I would hang some in Bhutan and some when I returned home. My kind and oh-so-knowledgeable guide, Kuenzang Norbu, researched dates that were bad to hang flags, and our wonderful driver, Tenzin Norbu (no relation) actually asked his father to research my best and worst days of the week.

Not long afterward, we were traveling over one of Bhutan’s many high passes where the wind rarely ceases. The peaks of the pass were a mass of poles bearing crowds of fluttering flags and I knew immediately that this was where I had to hang my flags. Wonderful Tenzin helped me sort through them and then our entire group climbed the hill with me and helped hang my flags.

Whether it was for my benefit or whether it was because we all received the benefit of hanging those flags in the wind, the giving nature of everyone involved (foreign photographers and Bhutanese hosts alike) left me quite astounded.

So, I stood in amongst all those windswept prayers and cried.

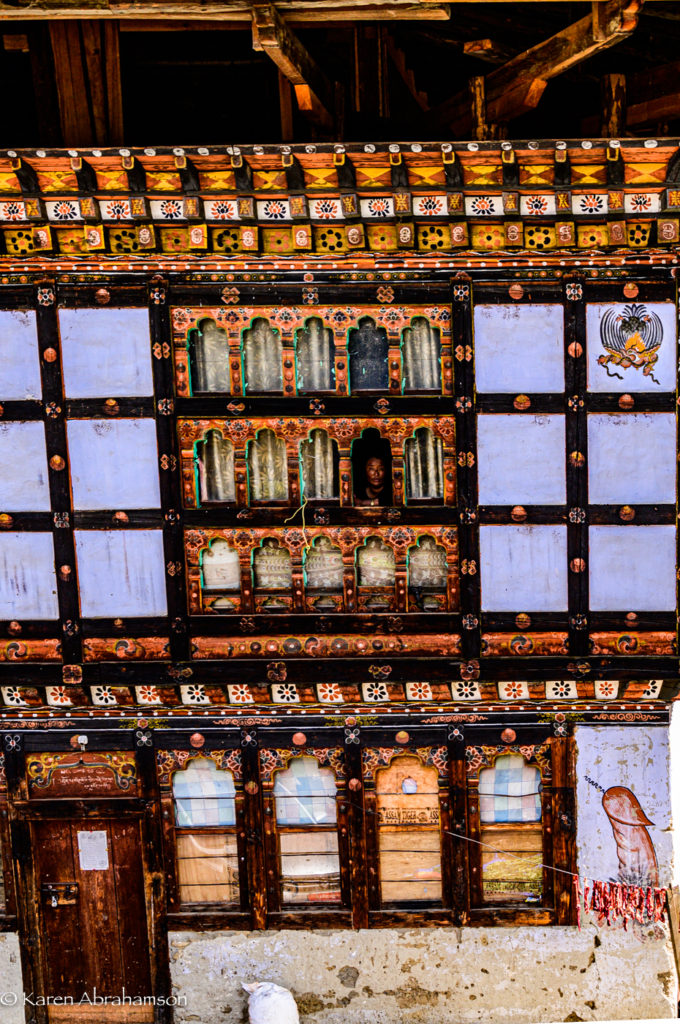

One of the images I will always remember of Bhutan is of the tall white walls and ornate carved lintels of the many monasteries and nunneries that dot Bhutan’s landscape. It seemed that beyond the mighty Dzong fortresses (that usually included a monastery), Bhutan’s landscape was littered with the gleaming roofs and walls of temples, monasteries and nunneries. Okay, that impression may have been added to by the prevalence of stupa and chorten (stone Buddhist monument, often containing religious relics) as well as smaller, white stone/clay structures found at homes, temples, monasteries etc. where people burn cypress or pine branches to purify the air. But within these glittering walls awaited the true jewels—the people.

On a personal level I can only imagine how invasive it must be to have camera-laden foreigners invading your place of quiet contemplation and snapping away. It must be even more so, when EVERYONE wants an image of a red-robed monk against a white wall. I can’t blame some of the monks for literally waving tourists away—heck, I’d most likely be doing a lot more to protect my privacy—but that wasn’t my experience with the monks and nuns of Bhutan.

Our first visit to a monastery was at Jakar Dzong. We arrived late in the afternoon after most tourists had come and gone. Not surprisingly, late in the afternoon was also when the monks ventured out, but I was surprised at how welcoming they were. Young monks posed for us, and one of the senior monks (he happened to be an adopted relation of our guide) invited us into his chambers to share a glass of arra, a powerful liquor distilled from rice, and some puffed rice. With all of us (seven photographers and two guides) crowded into his room and seated on the floor, our host proceeded to spend over an hour with us answering questions about Buddhism and monastic life.

That alone, was a gift, but he also invited us to an early morning ceremony at the temple so we were up and at the temple by 6 am—about 3 hours after the preparations had begun. There we sat at the end of the room while the monks chanted, blew long horns and beat ornate drums, while here and there the poor young monks would doze off for a few minutes before jerking awake again. I cannot convey to you the bone-deep vibration of the chanting and the soft yellow gutter of the butter lamps that illuminated the room.

On another occasion we visited a nunnery set on a hilltop a long way off the main roads. When we arrived most of the young nuns were too shy to allow us to photograph them, but with a little cajoling and a lot of laughter we finally broke through. The ‘hit’ of the day was a small polaroid camera that allowed us to take photos for the nuns to keep. It was wonderful and the smiles were beatific.

Maybe it was the time we took, instead of just swiftly touring around and snapping photos like so often happens with tourists, but it was nice to see the monks and nuns wave back when it was time for us to go.

I’ve been to festivals here in North America and elsewhere in the world. I’ve stumbled through religious and nonreligious festivities in Peru, Myanmar, Bali, Portugal and elsewhere in Europe as well as here in North America. All were colorful and all had excitement—the pageantry of a Jesus effigy led through the streets; the golden offerings of Bali; the color of Canada Day; or the raucous parties of the Fourth of July of my American friends. Not to mention the fireworks.

None of them have anything on Bhutanese Buddhist Monastic Festivals and I didn’t even attend the country’s biggest festivals in Thimpu or Paro, but these were the biggest, brightest, friendliest, boldest events I’ve ever been to. Think something like a major PRIDE parade on steroids.

Don’t get me wrong—there aren’t skimpily clad people running around –the Bhutanese are always chastely attired in their traditional Gho and Kira. But, well, there are plenty of phalluses. You see, because of its association with a Lama, the phallus is protective symbol in Bhutan and so you see them everywhere. Carved ones hang off the corners of homes, painted phallus adorn exterior building walls and more carved ones are set prominently above shop doors and windows. So, if you are shy of the human male member, don’t go to Bhutan. You’ll kill yourself blushing.

The phallus is also plenty visible at monastery festivals. Monk dancers spin around the open courtyards of these huge white strongholds, but around their edges, taunting and teasing the crowds are the ‘clowns’ (actually the most senior and best of dancers) carrying phalluses and teasing the crowds. Women and children giggle and hurry away. Men joke with these supreme joksters. At one point, one of my photographer companions was down on one knee taking a series of panning shots with his camera. The next thing he knew, he had a clown beside him, using the phallus to point as his camera, mimicking my friend’s actions. The clown got his reaction and my friend could only laugh in response.

Beyond phalluses, the Bhutanese were wonderful at welcoming a motley group of photographers into their midst. Monks and local villagers usually agreed to a photo and would pose for us. At one festival we were even allowed to enter the antechamber where monks prepared for their dances and to photograph the intense preparations they went through.

Best of all, though, were the lovely people who had come on pilgrimage to the festival and invited me to join them on their mats where they shared tea and roasted rice. Lovely and very tasty and they even tried to explain the characters of the various dances. It reminded me of other places and times and of the camaraderie of being seated on the earth and enjoying the company of the kind people you meet at festivals of this kind. It’s a chance to breathe in the spirit of a place.

Since returning home and while suffering from jet lag I’ve had a number of people ask me where I was travelling. When I answer “Bhutan” I’ve had a lot of blank stares, so just to clarify, Bhutan is a small Himalayan country pressed, geographically, between Tibetan China and India. In fact, both larger countries have, in the past, taken over parts of Bhutan, with the most recent encroachment being the Chinese moving into and claiming Bhutanese highlands. The Chinese were presumably driven by the need to claim more of the very rare and very valuable Bhutanese cordyceps—a fungus that grows out of a high-altitude caterpillar’s forehead that “purportedly has medicinal powers matched only by rhino horns, elephant tusks and tiger penises” (according to my Lonely Planet guide.)

So, Bhutan whose symbol is the thunder dragon and which enjoys a Tibetan style culture that is purely its own, sits partially in very high mountains and partially in lovely valley floors. The lowest of those valleys is apparently still higher than some of the lowest elevation cities in Peru—the last country that I visited where altitude was involved. Given how altitude sickness struck me in Peru (I couldn’t take the preventative drugs because I was technically allergic to it), I was more than a little paranoid about visiting Bhutan. The skull-shattering headaches I had in Peru made me think I might understand how the caterpillar felt when being attacked by the head fungus. So, in preparation for Bhutan, I decided to go through my own ordeal before I left on the trip. I decided to get tested to see if I really was allergic.

The altitude sickness drug is called Diamox and it is a sulfa-based drug, to which I am allergic (according to doctors that I saw when I was sixteen years old). In the interest of seeing whether my body chemistry had changed, my current family doctor referred me to an allergist—a referral that took three months before I had an appointment, putting me only one month from my Bhutanese departure date. I arrived at the appointment and the allergist took my blood pressure, checked my heart etc., told me that I was healthy (which I knew) and then advised that there were NO tests for sulfa allergies, but if I’d like to go into the hospital for three days they could possibly test me for Penicillin allergies. (I mean what the****?) He suggested that I not take the Diamox but, as an afterthought, suggested that I might want to call the local travel clinic for a second opinion.

Given my experience in Peru and my determination to go to Bhutan, that was exactly what I did. I spoke to the travel doctor who listened to my issue. She told me to take the Diamox—there was, apparently, no cross-reactivity (whatever that means). So I did that, too.

In Bhutan I travelled over passes that were 3,900 meters high and spent days at 3,300 meters—considerably higher than where I became sick in Peru (though at 3,300 meters I had frequent headaches even with the Diamox), but it was worth it. I even climbed a mountain to the Tiger’s Nest monastery at an altitude of about 3,000 meters and am here to tell the tale.

So the perilous Bhutanese landscape was really simply the magical landscape of the thunder dragon, Himalayan mountain peaks, picturesque plateaus and river valley’s so deep they looked bottomless. Everywhere there were towering cypress trees on the heights and rhododendron trees lower down. Rice fields heavy and ready to harvest lay along the valley bottoms and on stepped paddies up the valley sides. Dotting this landscape were the small towns and cities and the huge white-walled monastic fortresses called dzongs.

Most memorable of all were the beams of God-light shining through the clouds to spotlight white-washed temples or green fields. It was—supernatural, superlative, spectacular, breathtaking. And I was able to enjoy it all, thanks to the Diamox.

I pity the poor caterpillar who can’t enjoy the rarified heights where it lives.

In Bali the worldview is a trifle different than in the west. It’s based on the island’s geography and Hindu beliefs and leads to some interesting contradictions that I’m struggling to deal with.

The Balinese recognize the compass points of north, south, east and west, but they also have a unique take to their geography, namely that all good things come from the mountainous heights, while evil/badness comes from the ocean. I don’t quite understand this belief given they enjoy the bountiful seafood harvest of the coast, not to mention the planeloads of tourists who come to bask in the sand and sun. As for the mountains, at this moment Mount Agung seems perilously close to a major eruption—so much so that they’ve evacuated a number of villages from the mountain’s slopes. Agung even burped just two days ago!

I’ve also been struck by the environmental attitudes of the people on the island. On the one hand there is this genuine appreciation for the beautiful island they have inherited and the island has initiated efforts like the recycling of plastics (they ship them to Indonesia for recycling.) In the city of Ubud they’ve even been trying to eradicate single use plastic bags. On the other hand, the rivers near even the most holy of temples are filled with refuse.

We talked about this this morning and wondered whether it was a result of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. After all, in Bali job sites advertise jobs earning an average of 400,000 rupiah a month—that’s less than $40 US. When your focus is on earning enough to feed and educate your children (they have to pay for schooling here, not to mention for all medical care), maybe environmental issues aren’t at the top of your awareness.

There’s also the question of animal care. We’ve seen a number of philanthropic organizations for dogs and cats and frankly the cats and dogs we’ve seen have seemed healthy overall—probably due to those efforts and those of animal owners. I’ve been told that the Hindu beliefs recognize the souls in all plants and animals, and that the belief is that animals killed for food/sacrifice are blessed because they gave up their lives and will therefore be born human in their next life. All nice to hear.

And yet—the other day a small Bali Komodo lizard about 18 inches long surprised me by the pool—or I surprised it. The poor thing ended up in the pool and when I called someone to help it out, their response was to try to kill it. I don’t understand why—I mean I understand that in the old days the large ones (think as large as your leg) could steal and eat village chickens, but this was a small creature.

And then there’s the questions about tourists. On the one hand, Bali is a beautiful island that has benefited from its tropical mystique and the rich foreign dollars that have flowed into the country. My question is what are they losing in return? The rice paddies are being turned under to build tourist villas and more and more people are leaving the villages for places like Ubud. Talking to people it’s interesting that many are openly discussing how to retain the ‘Balineseness’ of their island in the face of pressures from many sources, like the fact that Indonesian has been the language of choice of higher learning, and the challenge of marketing their culture yet retaining the culture’s authenticity.

One of the things the Balinese have done well is to foster the retention of their art forms. Dance schools thrive and many girls and boys study dance at least for a while. Villages exist that focus on painting, silver smithing, stone carving, gamelan making, and woodcarving, amongst others.

And yet, again, to my western eye there is a dark side. When I ask staff of one of the teak shops or carving studios where the teak comes from, they tell me not from Bali. No, they want to save their jungles. Instead, it comes from places like Sumatra or Borneo—places I know are suffering from deforestation and environmental degradation, impacting endangered species like elephants and orangutans.

So, I’m leaving Bali with mixed feelings. I love the people and so much about the culture and how the place where I’m staying has made me feel like part of the family, but I’m clearly a foreigner with foreign questions, concerns and definitely a different worldview. Visitors who have been coming to Bali over the years say the place has changed in so many ways, from the changes brought by Indonesia’s attempt at democracy, to the growth in the tourist industry and the increase in traffic congestion.

If I return (and the sadness I feel at leaving suggests that I might) it will be interesting to see how the Balinese solve these dilemmas.

Inevitably, whatever is done, will be in a unique Balinese style.

It’s February 23 and it’s the day after the birthday of the temple around the corner—thank goodness. I don’t have to go running out for photos of the events. Maybe tonight we can even get a full night’s sleep.

This temple happens to have a congregation of over a thousand families, the largest in the Ubud area. It’s a big deal. For the past five days throngs of people have brought offerings to the temple—think platters and bowls stacked with pineapple, papaya, mangosteen, oranges and even the exotic (to Bali) apple, pear or grape. Flowers, rice, bread, even packaged foods are placed in decorative heaps in beautifully woven, hand painted, gilt and even beaded bowls and carried on women’s heads to the temple where they are stacked until after prayers and then taken home again—where they are eaten by the family who brought them.

The processions are a lovely part of Balinese culture, one I’ve already written about here, but there are many more lovely parts of this island. First of all, there are the numerous temples so that there seems to be one around every corner. Some are locked off to foreigners, but many have opened their doors—at least partially. Take for example, the lovely water temple, Tirta Empul, that offers Balinese and foreigner alike the opportunity to cleanse themselves in purified water from holy springs as well as the chance to cleanse their minds in the quiet corners listening to the priest’s bells that act as a focus to prayers.

Probably the first moment of ceremony that I stumbled over in Bali was a small woven basket with flowers blossoms, a bit of fruit, rice and incense left in a doorway that I literally stumbled over as I went out one morning. These bits of beauty are everywhere, placed there daily usually by a housewife carrying a wicker tray of such things. They stop at shrines or seemingly nondescript places or at gates or doorways and quietly light an incense stick, place it in the basket of blooms and place the whole thing at the doorway. A single exquisite flower bloom held in the point of their fingers as they say a short prayer and then the blossom is placed in the basket, too. And then the woman moves on to the next spot they wish to make offering to. Each day the pavement is littered with flowers and each morning they are swept up and replaced with the same quiet attention to recognizing the precious places around them. It’s a lovely recognition of the sacred in all places.

The birthday of the local temple wasn’t quite so quiet. First came the processions down the street. They are special for this temple because of the stature and age of the temple. Each one is a procession from another temple that has a relationship with this one. Some arrive from close by, but others come by truck from far away and form their procession a few miles away. Each one brings with them their good and evil demons and, more importantly, their holy barong.

A barong is an important Bali spirit. My local informants couldn’t really say where the barong came from, though they think the roots could be in the Chinese dragon, but I wonder if it might have a heritage in the now extinct Balinese tiger, because the creatures have fur coats (some striped) and vaguely cat-like features and when they dance, their movements remind me of cats, too. Either way, there is power in the barong and they reside in various temples. Some barong have ancestral relationships with the neighbourhood temple and so they have been brought from very far away.

Which brings me to the sleepless nights.

Barongs don’t travel alone and they don’t travel silently. Every barong travels with his own orchestra of flutes and drums and—wait for it—gongs. These are pie plate sized and worn like a xylophone, or two – three feet across and carried by two men, or even three gongs on a cart that is wheeled along with the gong player seated in the middle. It’s a regular cacophony of drums and gongs—lovely to listen to except at 3 am.

So the temple ceremonies took place over three days and the barong processions occurred where and when the temple priests decided. That meant traffic havoc for Ubud because the three main roads in the town would have to shut down. Each evening at the temple, there was a performance, the first night of dancers and orchestras, the second of dancers, orchestras and a stage barong (as opposed to the holy temple barong.) Each of these sessions was wonderful, with the dance and the music and I stayed taking photos until 9 or 10 pm, but the performances went on long into the wee hours after I got home and of course sound travels…

The third night was the finale: a public performance of dance and barong dancing using the true temple barong. At 8:30 the first of the dancers danced and then the first barong performed—a halting dance of a great beast cautiously treading through the land. The dance ended and they brought out the second barong who was every bit as cautious.

Okay. I’d seen the holy barong dance.

Okay, I’d seen the holy Barong–I thought. But I was tired and the performance was, I must admit, a little underwhelming. So I decided to call it a night and went home. Only to be disturbed as I was falling asleep by the horrible sounds of beast roars and narrated screaming.

Clearly, I had gone home at the wrong time. Clearly the barong had come upon a warrior and the battle had been begun. There was music and more roaring but I must have been very tired because I finally fell asleep—only to be woken a second time at about 3 am by the sound of drums and music in the street.

I tracked it from my bed: Approaching from the temple eastward and drawing even with my guest house gate and then heading westward down the street.

The sound of a vanquished barong headed home.

For all I love the Bali culture, I appreciated that I could finally sleep in peace.

Bali is a place built on rice (and tourism, but we’ll leave the tourism for the moment.) I’m staying in Ubud, one of the main tourist towns in Bali (the one made famous by Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love.) It’s a busy place with a perennial traffic jam and stores that run the gamut from a fruit stall on the corner and cheap restaurants in people’s homes, to couture clothing stores, starred eateries that require a reservation, and Starbucks on the corner. It’s also the kind of place that you can come around the corner and find a rice paddy between two rows of houses and where all the tourist maps include trails through the extensive paddies around the town.

Rice is everywhere: from on your dinner plate, in the innumerable small offerings to the spirits found pretty much everywhere, and even on people’s foreheads when they leave the temple. It comes in colors like white, brown, red and black and I’ve discovered that from amongst that rainbow, I enjoy rice far more here I ever thought I would as I grew up eating the insipid Uncle Ben’s. Yeah, sure, I cook basmati at home, but even basmati is tasteless compared to what I’ve eaten here.

But more than learning to appreciate the nutty flavor of whole red rice, or the sweet goodness of black rice for breakfast, being here has brought me closer to a different understanding of rice in the world. I suppose it’s more of a metaphor.

Bali might be a Hindu island in a Muslim nation, but Bali’s animistic roots are never more evident than in their relationship with rice. Central to the Hindu faith is that God has many manifestations, not just the Trimurti of Vishnu (the creator), Brahma (the maintainer) and Shiva (the destroyer.) God also manifests in the person of Dewi Sri, the rice mother, who receives offerings in shrines built in every rice field. Some shrines are only small wicker platforms built above the rice. Others are more complete structures, but their purpose is the same—to give thanks to the rice mother for the harvest to come. Small offerings of rice, a flower and perhaps incense are left daily to Devi Sri.

I suppose it’s not surprising that the farmers believe they need the help of the spirits/gods in order to have good harvests. Rice farming is back-breaking work. First the rice is planted in a nursery spot, usually at the corner of the field. Preparing the rice paddies involves plowing, loosening of the soil of the flooded paddy, and then flattening of the soil in preparation for planting. Bali has only recently transitioned from bullocks pulling plows to hand-pushed rototiller machines. Talk about back-breaking.

When the young plants are old enough, they are manually uprooted, separated, and replanted in the prepared rice paddies. Think of spending days and days under the unrelenting sun planting individual plants exactly a hand-span apart in rows so perfect, you’d think they’d been laid out on a grid. More backbreaking. Gradually, the plants mature, and then the harvest takes place with old fashioned scythes. It’s no wonder that young people want to leave the farms for opportunities in the cities or in places like Ubud.

Walking the rice trails, one is struck first by the intense green color, by the egrets dotting the fields and the calls of smaller song birds that accompany the music of water. There is water everywhere, standing in sky-reflecting paddies, running down ditches between the fields and gushing down channels built to guarantee that all farmers’ fields share in the gift of water. In Bali there is a rice farmers’ water cooperative that manages this sharing. They have a governance structure and their purpose is sharing the wealth nature gives them—so much so that their water system is recognized by Unesco World Heritage. There’s even a museum to rice and the water management system, though when I visited it was rather abandoned looking. The information was there, though, when I looked past the cobwebs.

All of this has led to my new appreciation of rice. Like life, it is a gift of the gods. It is also the product of heavy labor by many, many people.

As the Balinese do when they place their offerings to Dewi Sri on the bamboo platforms at the edge of the fields, I want to think about the manifestation of the God and the labor it took to provide EVERY SINGLE GRAIN OF RICE on my plate.

And be thankful.

(Yes, I know that in North America big Agro companies provide our rice with little of the labor that I’m seeing in Bali, but from now on I’m going to be more conscious about where my rice comes from. Surely it can only be beneficial to eat food grown with the intention of being in harmony with nature, instead of food grown as a product of genetic manipulation! No wonder North American food is largely tasteless.)

We’ve been in Bali ten days now and it has been a wonderful lesson in exploration—both sensory and experiential. For instance, at the moment I’m in my bed listening to a thundering downpour and the quintessential sound of gamelan music played for a Balinese shadow puppet show.

But not every experience has been quite so mesmerizing. At least they haven’t all been quite so easy to enjoy. Take for instance my first experience at my current guesthouse in the tourist mecca of Ubud. Ubud sits on the lower slopes of Bali’s central mountains and is a mecca for artists from around the world. Think wood and stone carving, silver smithing, weaving, painting and just about anything else you can imagine. We arrived at this guesthouse and our host knew of my interest in photography, so he immediately told me that there was a temple ceremony occurring that afternoon at a local community—come see him at three pm and he’d arrange for me to attend.

I showed up with camera in tow and the only way to get there was via motorcycle—him driving and me on the back. Let me just say that my distrust of motorcycles goes way back to my teenaged years and age and wisdom has only confirmed that opinion.

But it was a temple ceremony and I was new to Ubud. Who knew whether I’d get such a chance again. So I slung my leg over the motorbike behind him and drove—sans helmet because he didn’t want to have to carry an extra helmet back—to somewhere in Bali.

And he dropped me off.

Yes, I had his email and phone number on Whatsapp. Yes, I knew the name of the guesthouse and generally where it was in Ubud. But that was all. And oh, yes, I know how to say hello and thank you in Balinese.

But there was this temple ceremony, that it turned out I couldn’t attend because I didn’t have a proper sarong…

So I hung around outside with the parents with unruly children and the Balinese marching band (think gongs, conches for blowing, and lots and lots of drums.) Luckily, the Balinese are big on processions, because after what sounded from outside the walls like a lovely ceremony, the dignitaries left (would you believe it was the royal family of Ubud?) and were followed by a flood of people.

I ran up the road to get a better view and what followed was a village procession. The photos in this post tell the tale. A non-marching band. Children dressed up like princesses. Women carrying offerings on their heads and men carrying even larger offerings on platforms. And all the people in their finest sarongs and sashes. They marched up the road with so much laughter and friendship that I was swept along—until they reached another temple and I was shut out again.

Darned no sarong.

And then I had to figure out how to get home…

From somewhere in Bali.

P.S.

(Yes, after realizing that my Whatsapp messages were being routed via North America so there was a time lag, I finally contacted my wonderful host by phone and he sent his son to rescue me. So I am no longer lost.)

We’ve been in Bali since February 4thand the first word I have learned is ‘Salam’, or ‘hello.’ I swear we are both still recovering from our Indian sojourn, which seems odd to me given basically all our travel arrangements were made for us. But then again, when there are issues the stress can wear you down and our trip through India was not without issues. But that’s another story.

For the moment, we are in Bali and trying to sink into the Balinese culture and balance.

We spent the first few days in a place called Jimbaran that is on the coast, south of the major city of Denpasar and the tourist haven of Kuta. We arrived and both of us were overwhelmed by the beauty of our residence. We had a room with sliding glass doors onto a balcony and small plunge pool overlooking the Balinese beach of Jimbaran. It took us a few days to realize that we were right above the Four Seasons resort at less than a quarter of the cost and we were staying in a heritage building owned by an architect who was committed to maintaining the jewel that he had.

A ten-minute walk downhill had us on the sweeping crescent of Jimbaran Beach where I collected shells and, in the evening, we went to a dinner of barbequed, squid, clams, fish, prawns and lobster for about $30.00 each. The seafood, with the addition of rice and water spinach was to die for and as an added bonus we were treated to a spectacular sunset. I’m told that every sunset is just as good.

We visited one of the three key ocean temples in Bali, this one called Ulu Watu. We intended to watch the sunset and the sunset Kacek dance. Unfortunately, you can’t actually do both, or at least you can’t watch the sunset over Ulu Watu because the temple is in the wrong direction from where they hold the dance, so the dance won out. While the dancers wear the ornate costumes that you might associate with Bali, the dance itself is actually quite original—at least at Ulu Watu.

The performance begins with about thirty men who come into the performance area chanting, to settle around a tall, wooden candelabra-type stand that has small flames lit on each of its arms. They chant and then, one by one, the dancers entered telling the story of Rama and Sita out of the Ramayana. The difference I saw in this dance compared to the dancers from the performance I wrote about in Kochi, was that these dancers seemed to move in utter, perfected, slow-motion.

Except for Hanuman.

The mischievous white monkey god was up to his tricks from the moment he entered the story, leaping into the story from on top of the gate, and climbing up among the audience, stealing hats and glasses and picking imaginary nits out of people’s hair.

Anyway, the performance was wonderful, Sita was rescued, the evil Ravana was vanquished, and everyone except Ravana lived happily ever after—except for us, because traffic leaving the temple made us endure a trip home that was well over an hour long.

But it was a good introduction to Bali. We’re both impressed, not least of all by the driving. Though there are a lot of cars and motorbikes on the road it’s not the bone-jarring, psyche-scarring, free-for-all we survived in India. Instead, here traffic more or less obeys the traffic lanes and vehicles will actually stop for a pedestrian.

That brings me to the second Balinese word/phase I’m trying to remember: terima kasih, or thank you! Terima kasih for these past few days, Bali.