Books and Geology: Mapping Beneath the Surface

Recently I was reflecting on the difference between plot and story, with plot being the events that happen to keep the story moving, and ‘story’ being what the book is about and the changes that occur to the characters along the way. Frodo starts out as a happy young hobbit, and returns as someone who understands the price that must be paid for the safety of places like the Shire. Bella starts out as this infatuated, clumsy girl who constantly has to be rescued, and turns out to hold the secret abilities to save everyone.

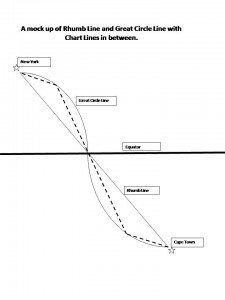

This got me thinking about mapping beneath the surface. In a book, if you are a plotter, you map out where the actions occur, but also the impact the scene has on the character. I started out writing this way, and used wonderful planning sheets like these. This has allowed me to layer stories with the emotional changes that make a story much richer to read.

A similar process has occurred in mapping the world. Once the surface mapping was well under way, people began to wonder how to map the landscape under the layer of dirt and forests we see. Why? To gain a better sense of the layering of the landscape and the connections between places. For example, the discovery of similar strata layers in both France and England demonstrated that once they were a single land mass.

The process of mapping the underside of the earth began around 1750 when a Frenchman named Jean Etienne Guettard asked just such a question about England and France. Though he posed the question, the first person taken seriously for geological mapping was an Englishman named William Smith who spent a quarter of a century mapping England and Wales beneath the ground. Smith had been a surveyor’s helper and a keen observer who noticed and recorded things like strata exposed in hillsides and in mine shafts. Smith was the first person to have the insight that different strata held different fossils from different time periods, which provided a means to date the strata. He also noted that similar fossils were found in similar strata, even though they were separated by long distances. In 1815, the result of his study was a many-colored map of England and Wales that set out the different geological formations.

Such a map can set out the distribution of various geological units such as glacial debris (if it was near the surface) or deeper formations like igneous, metamorphic or sedimentary rock that underlie the topsoil. Of course, having a general picture of the structure of the earth wasn’t enough for a civilization with an increasing thirst for oil and minerals, so processes were developed that measured gravitational attraction from which geologists could deduce the nature of the subsurface geology. Other processes drew on the ancient Nordic use of magnets to locate ore bodies. A more modern magnetometer was developed in the 1930s and mounted on aircraft to gather readings. The Seismic method was developed after 1875 when an English geologist in earthquake-prone Japan, thought to use a seisomograph to determine where the quakes arose from. A similar process was used in 1909 to discover the boundary between the Earth’s crust and its mantle.

Using sonic sounds or thumpers or vibrators to create sound, the sonic process then uses geophones (or hydrophones for underwater exploration) to read echoes from underground formations that tell the scientists what lies underneath.

This has led to the ability to measure the crust of the earth (which measures from about 6.5 kilometers thick under the ocean to 50-75 kilometers thick under high mountains), the mantle which extends from the crust to about half way to the centre, and the dense, partly molten core. Seismology has led to the ability to map oil deposits and layers of water and natural gas that wait in the earth’s crust. But they have also allowed scientists to reach much deeper.

Geologists are now able to measure and map the underside of the earth’s crust (I alluded to this here). Which is a lot like understanding the underside of a novel, because, like the geothermal power of the earth that may save us from global warming, it’s really the hot emotional underbelly of a novel that brings out the best of any novelist’s writing.