Bhutan: How to Host a Festival

I’ve been to festivals here in North America and elsewhere in the world. I’ve stumbled through religious and nonreligious festivities in Peru, Myanmar, Bali, Portugal and elsewhere in Europe as well as here in North America. All were colorful and all had excitement—the pageantry of a Jesus effigy led through the streets; the golden offerings of Bali; the color of Canada Day; or the raucous parties of the Fourth of July of my American friends. Not to mention the fireworks.

None of them have anything on Bhutanese Buddhist Monastic Festivals and I didn’t even attend the country’s biggest festivals in Thimpu or Paro, but these were the biggest, brightest, friendliest, boldest events I’ve ever been to. Think something like a major PRIDE parade on steroids.

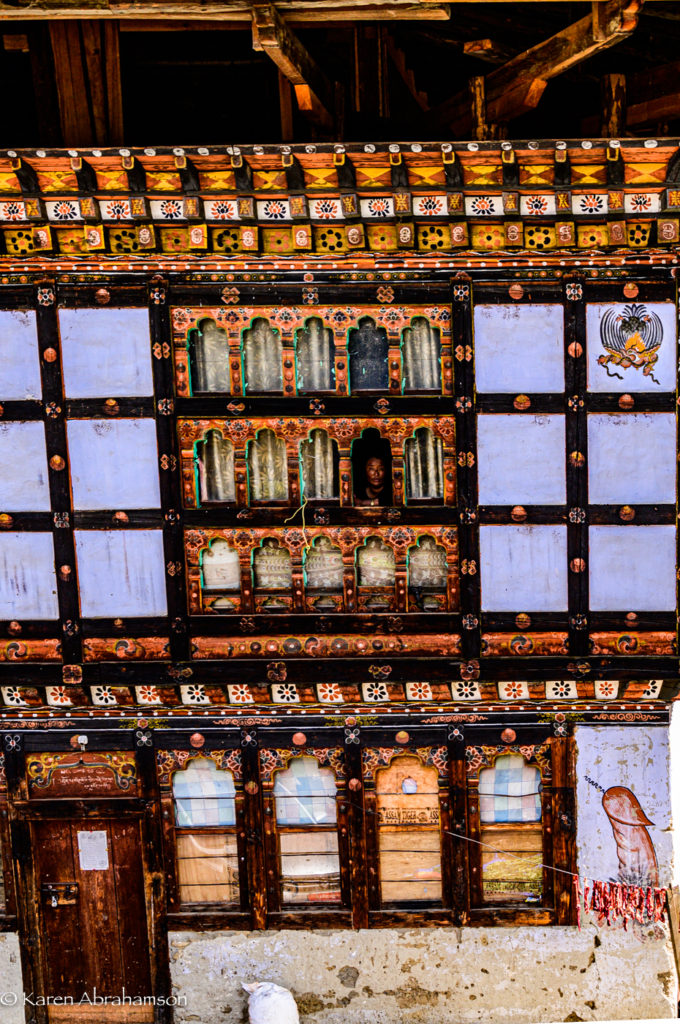

Don’t get me wrong—there aren’t skimpily clad people running around –the Bhutanese are always chastely attired in their traditional Gho and Kira. But, well, there are plenty of phalluses. You see, because of its association with a Lama, the phallus is protective symbol in Bhutan and so you see them everywhere. Carved ones hang off the corners of homes, painted phallus adorn exterior building walls and more carved ones are set prominently above shop doors and windows. So, if you are shy of the human male member, don’t go to Bhutan. You’ll kill yourself blushing.

The phallus is also plenty visible at monastery festivals. Monk dancers spin around the open courtyards of these huge white strongholds, but around their edges, taunting and teasing the crowds are the ‘clowns’ (actually the most senior and best of dancers) carrying phalluses and teasing the crowds. Women and children giggle and hurry away. Men joke with these supreme joksters. At one point, one of my photographer companions was down on one knee taking a series of panning shots with his camera. The next thing he knew, he had a clown beside him, using the phallus to point as his camera, mimicking my friend’s actions. The clown got his reaction and my friend could only laugh in response.

Beyond phalluses, the Bhutanese were wonderful at welcoming a motley group of photographers into their midst. Monks and local villagers usually agreed to a photo and would pose for us. At one festival we were even allowed to enter the antechamber where monks prepared for their dances and to photograph the intense preparations they went through.

Best of all, though, were the lovely people who had come on pilgrimage to the festival and invited me to join them on their mats where they shared tea and roasted rice. Lovely and very tasty and they even tried to explain the characters of the various dances. It reminded me of other places and times and of the camaraderie of being seated on the earth and enjoying the company of the kind people you meet at festivals of this kind. It’s a chance to breathe in the spirit of a place.