Myths, Latitude and the Financial Shape of the Earth

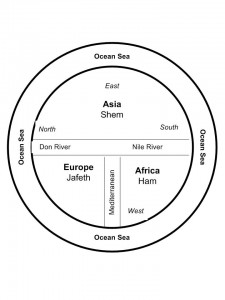

Despite the myths and rumors of a flat earth promulgated during the Middle Ages, most scientific minds over the centuries have known the world was a sphere. Clues to this came from the fact that boats sailing away disappeared gradually as if they sank from view, and did not simply diminish in size. The Greek philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras, hypothesized that earth was a sphere based on the fact that the sphere is ‘the most perfect of forms’. If the sun and moon were such a shape, why not the earth? It was Pythagoras and other Greeks such as Plato and Aristotle who cemented the idea of a spherical earth in European culture.

Despite the myths and rumors of a flat earth promulgated during the Middle Ages, most scientific minds over the centuries have known the world was a sphere. Clues to this came from the fact that boats sailing away disappeared gradually as if they sank from view, and did not simply diminish in size. The Greek philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras, hypothesized that earth was a sphere based on the fact that the sphere is ‘the most perfect of forms’. If the sun and moon were such a shape, why not the earth? It was Pythagoras and other Greeks such as Plato and Aristotle who cemented the idea of a spherical earth in European culture.

So people knew the world was round, they just didn’t know the size of it, nor did fully understand its shape.

Estimating the size of the earth also harkens back to the Greeks. Both Aristotle and Archimedes had erroneous estimates of the earth’s circumference, but history hasn’t left any clues as to what those estimates were based on. The

Chinese apparently sent two men to measure the earth and they walked it from north to south and east to west before coming up with the result of 134,000 kilometers (hopelessly in error).

The first (known) scientific measurement of the earth’s circumference came from an Egyptian named Eratosthenes during the time of the Ptolemy Kings. He knew of a water well in Southern Egypt where at noon on a certain day of the year the sun shone straight down to the bottom. He also had made observations that on the same day in Alexandria, at noon, there was still a shadow. He hypothesized that if he could measure the angle of the shadow on that day, he should be able to estimate the size of the earth. Using a vertical column he did just that, measuring the distance of the shadow from the base of the column. Then, with the length of the column, and the length of the shadow, he could calculate the third side of the triangle and determine the angel of the sun’s rays. Using basic geometry he was able to hypothesize that the earth was 46,000 kilometers in circumference – too large since we know today that the circumference is about 40,000 kilometers – but not too shabby for a man working with only a shadow and a column.

The debate about the actual size and shape of the earth continued over the centuries, with various other size estimates coming to prominence at different times. Contributing to the issue was the debate over the actual length of a degree, a debate that raged for centuries. This led to numerous ‘thinking men’ attempting to determine the length of a degree through methods ranging from counting the turns of a carriage wheel as it travelled between two points, to taking laborious chain measures of distance across the English countryside. It took debates of Newtonian and Cassini theories to help scientists realize that they were – in a word – wrong – about there being a definitive length of a degree.

You see, Newton formulated the theory of universal gravitation and that centrifugal force would mean that the earth could not be perfectly round. If he was right, due to the earth’s spin, the earth would be flattened at the poles and would bulge at the equator. Refuting this was the work of French scientist, Jacques Cassini, who had found that the length of a degree seemed to get slightly shorter at the poles compared to the equator. He theorized that this meant that the earth was shaped more like an egg, with poles drawn out and the equator flattened.

It took two expeditions in the 1700s, one to Peru and Ecuador, and other to Lapland, to settle the issue. While the trip to Peru dealt with altitude sickness, unfriendly Indians and disease, the expedition to Lapland had to race winters to take measurements. The team in Lapland completed their measurements after two years and found that the length of a degree was significantly longer in the north than a degree measured in France, thus proving that the earth was indeed compressed on the poles and bulging towards the equator. The poor Peruvian team spent nine years completing their mission, and confirming Newton’s theory, only to discover that their work was redundant.

It took two expeditions in the 1700s, one to Peru and Ecuador, and other to Lapland, to settle the issue. While the trip to Peru dealt with altitude sickness, unfriendly Indians and disease, the expedition to Lapland had to race winters to take measurements. The team in Lapland completed their measurements after two years and found that the length of a degree was significantly longer in the north than a degree measured in France, thus proving that the earth was indeed compressed on the poles and bulging towards the equator. The poor Peruvian team spent nine years completing their mission, and confirming Newton’s theory, only to discover that their work was redundant.

But what they showed was that the length of a degree will depend on the latitude:

- The east-west degree at the equator = 111.321 kilometers, however the circumference along a meridional circle is 67.2 kilometers shorter.

- The north-south degree at the equator = 110.567 kilometers and the

- The north south degree at the poles = 111.9 (or 1.4 km longer)

All of which may be where the phrase ‘giving someone some latitude’ comes from: What they do (and how far they go) will depend on where they’re standing.

Which could explain the disparity in approach the Germans and Greeks are espousing to deal with the Eurozone financial crisis. It’s all latitude.