Free Fiction

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

Jaymee and David’s saga continues. To read Chapter 21 and 22, click here.

I fell off the map this week – at least that was what it felt like when I learned that I’d been removed from the intercom list at my townhouse complex. It doesn’t sound like much – a simple omission when they were doing the complex list – but think about it. To the outside world I no longer existed in this location. I inhabited an invisible place outside of the normal world that happened to be located between the house number below me and the one above – much like the safe house in Harry Potter but without the overt magic. I was gone, and so was my home and all the mementos I’ve collected from across the world. And of course my cats.

I’ve experienced something similar before, when I worked in the interior of British Columbia in a small town that was a long ways away from anywhere. When my agency’s reporting relationship shifted from one region to another, all the paperwork connections seemed to disappear and no one contacted us – it was actually quite a nice change. But it was also like we inhabited some huge fog bank that filled a space in the center of the province that no one knew existed. Our own personal twilight zone.

Such phenomena isn’t only in my imagination. Cartographers have been erasing or omitting bits of the landscape from their maps since before Prince Henry, when choice harbors and trade routes were secrets worth killing for. In order to gain a truer picture of the world, it became common practice for Kings to confiscate the log books and charts of each ship that came to harbor in order to copy them down before the sailors took ship again.

During the time of the early Portuguese spice trade, the location of, the Moluccas, the five tiny islands that were the sole source of nutmeg, mace and cloves, were closely guarded secrets. True maps of the eastern Indian Ocean were treated as highly classified documents (and few exist today) due to the possibility that the Portuguese were violating a Papal bull which gave the Spanish sovereignty over all lands west of a longitudinal line running 100 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands (in the Atlantic).

During the age of exploration and when Spain, France and England were vying for the Americas and the Northwest Passage, maps were made that purposely misrepresented the landscape in case they fell into (and sometimes purposely intended for) the enemies’ hands. Such maps were intended to deter exploration by competitor nations because the harbor, the river, the inhabitable, productive land wasn’t there.

Even today we see maps shift reality so that places exist differently than what you would find ‘if you were on the ground’. Road maps often include streets that are planned, but have never been built, or don’t describe that the street crossing that looks so direct on the map, can’t be made. A recent internet report showed that Chinese government maps of cities often change the position of major streets. Why? For military purposes. The government has apparently fallen back on the ancient practice of redrawing reality to stop potential invasion or intelligence gathering.

Happily, I’ve been replaced on the list of existing residents of my complex and so my home and I have been returned to reality. There is no longer a fog where my house once stood and my cats and I are all okay.

Free Fiction brings bleak times for Jaymee and David. Chapters 19 and 20 are up here.

Free Fiction brings bleak times for Jaymee and David. Chapters 19 and 20 are up here.

For men like Fra Mauro (see last post), the exploration of the external world led to an understanding of the inner landscape of men. So too, from the triangulation of the world (see post here) came a greater understanding of the internal shape of the earth.

I mentioned previously that in order to determine the shape of the world, a French survey team went to Ecuador and Peru at the same time as a team went to Lapland. Unfortunately for the Peruvian team, the Lapland team discovered the answer to the scientific question long before the Peruvian team ever finished their survey. While in South America, however, the Peruvian team struggled over mountains and through jungles and noted different gravity readings as they took their survey measurements along their route. They surmised that the differences in the readings might reflect the varying landscape and theorized that mountains might be made of less dense material than the lowlands. A good theory, but it took over a hundred years for the matter to be more fully explored and the discovery was made far from South America. It took the British Raj’s need to survey India to bring understanding to what the mass of mountains might mean.

In the mid nineteenth century, the horrendous task of surveying India through triangulation was almost undone by the discovery of an error of some 150 meters between the distance the triangulation measurements computed, and an actual direct surface measurement. To determine what had led to the error, the cartographers involved had to reexamine their assumptions – in this case they had assumed that the mass of the Himalayan Mountains would greatly influence the gravity measurements of their survey instruments. What they found was that they had overestimated the lower mass of the mountains.

This led to a theory of the earth’s crust that still exists today, namely that every (theoretical) column of the earth (from core to outer surface following a theoretical plum line) should have approximately the same mass. Given that tall mountains have a lower mass, they must have an equally large (but low mass) protuberance at the bottom of the earth’s crust to achieve the same mass as denser areas of the earth’s crust. Conversely, under the oceans where the ocean basins are very dense, the earth’s crust would be relatively thin. The theoretical result would be that inside the earth there would be a mirroring of the plains, mountains and ocean valleys we see on the surface, much like a tall iceberg has a large underwater presence to balance it out. Modern science has supported this, by obtaining crust measurements off the coast of South America that show the Andes have roots as deep as 75 kilometers.

Think of this the next time you are crossing the mountains, staring up at those tall, snow-covered peaks, for they are the frosting, the outer conceit of an iceberg of stone that conceals the deeper reality of the roots of the mountains.

Much like Fra Mauro saw the illusions of men obscure the truth of his map of the world.

I want to apologize for missing last week’s posting of new chapters in Jaymee and David’s story, but a family emergency kept me away from the right material on my computer, I hope this week’s installment keeps you reading. Click here to read chapter 17 and 18.

I want to apologize for missing last week’s posting of new chapters in Jaymee and David’s story, but a family emergency kept me away from the right material on my computer, I hope this week’s installment keeps you reading. Click here to read chapter 17 and 18.

The other day at Powell’s Books (Portland), I came across a wonderful little book called “The Mapmaker’s Dream” by James Cowan. The book is the translation of the diary of Fra Mauro, a sixteenth century Venetian monk and cartographer who set out to make a perfect mappamundi (map of the world) though he had never stepped outside the confines of his cloisters. Instead he gathered travelers’ tales through exchanges of letters or interviews of missionaries, merchants and soldiers travelling through Venice. His task became well known and he received envoys from as far afield as the court of the Chinese Emperor. Not only was this book astounding for the fact that word of his venture travelled so far in the 16th century, but the information he collected and the workings of his mind fascinated me.

Yes, his travelers brought stories of the Cyclopedes, beings in the southern hemisphere with only one huge foot that they used for hopping and also for shade when the sun in the antipodes became too fierce, but envoys also brought other tales that caused good Fra Mauro much reflection. This was what captured my attention for they showed a keenness of mind and a shifting view of the world much like new age philosophers. This seemed strange for his time; given Fra Mauro was a devout Catholic.

His encounters left him pondering whether the soul could possibly transmigrate into another person upon the death of the body and whether we are ‘all drifting towards a more complete life in someone else’. The visit of an old Jewish merchant from Rhodes left him contemplating how the loss of place (in the holy land) ‘condemned the man to inhabit his loss forever’ and how the rootless person came to inhabit a region of his own mind instead.

Visits from others left him considering how venerated holy relics become something more because of that veneration, and how those objects take on their own life because they unite an idea that men aspire to. They left him wondering at cultures that worshiped Satan and yet were not evil, and others that determined their actions and their future through the calls of seven forest birds.

But most of all he wrote of the minds of travelers. He was struck by the notion that travelers not only travelled with their bodies, but also that they travelled in their minds and were transformed by that travel or, alternatively, transformed the place they had been. He wrote of the journeys of envoys sent to find the mythic kingdom of Prestor John and looked at the evidence of such a kingdom – the long letter still held in the Vatican archives that describes a kingdom so perfect it could not possibly exist. Fra Mauro concluded that the reason the search for Prestor John’s kingdom became all consuming, was not just the desire for aid against the Moslem hordes, but the desire to know that it was possible for paradise to exist on earth. Travelers longed to become ‘slaves’ to Prestor John’s perfection and bounty. But the country of Prestor John would never be found because it was only built on dreams.

Ultimately, Fra Mauro realized the challenge of creating a perfect map arose because each man’s perceptions of place were different and any ‘perfect’ map must capture not only the land forms, but also the forms of the world created by men’s minds.

The lowly monk of Venice completed his life’s work, but today no trace of his perfect mappamundi exists, except in references in the pages of his journal. Perhaps, like the worlds he described, it faded away to become the world as we know it today, but more importantly what his journal shows is a man of deep thought who’s Sixteenth Century perspectives still resonate with readers today.

Thank you, Powell’s, for this gift.

We have a lot to thank the ancient Greeks for. They gave us Greek culture, mythology, the Odyssey and the Iliad. They developed drama and many of the arts and sciences and gave us some of the best early approaches to understanding the world – including its cartography. But the Greeks got some things downright wrong, too, like the circumference of the world. Unfortunately the rest of the European world held onto these errors as gospel simply because it WAS the Greeks who initiated the theories.

We have a lot to thank the ancient Greeks for. They gave us Greek culture, mythology, the Odyssey and the Iliad. They developed drama and many of the arts and sciences and gave us some of the best early approaches to understanding the world – including its cartography. But the Greeks got some things downright wrong, too, like the circumference of the world. Unfortunately the rest of the European world held onto these errors as gospel simply because it WAS the Greeks who initiated the theories.

Case in point was the Greek philosophers’ belief in symmetry which, in cartography, surmised that because there was a large landmass in the northern hemisphere (Europe and Asia and North Africa), there must be a similar large land mass in the south. This led to world maps carrying the weight of a large continent south of the equator. In earlier maps this continent encircled the Indian Ocean, but when Vasco da Gama sailed the Cape ofGood Hope to circumnavigate Africa, the great continent receded a little, and simply reached out from the limits of Antarctica. It became known as Terra Australis.

The myth of the Antipodean continent caused cartographers to override the information brave explorers brought back from their ventures. When Magellan made the dangerous crossing from Atlantic to Pacific off the tip of South America, they spotted Tierra del Fuego and surmised it was an island. Cartographers, however, chose to override those who had been there, and drew Tierra del Fuego as an outcropping of the great continent. More mapmakers embellished their maps with prominent features like the land of Parrots, the Cape of Good Signal and the River of Islands, all lending credence to the existence on the continent. But exploration in the Pacific continued to chip away at the continent’s size, but it was only in the 1770s, when Captain James Cook was instructed to search for the southern continent, that he sailed farther south than 71 degrees to a land of fog and snow mists, that cartographer’s gave up on their belief in the super-sized southern continent.

The myth of the Antipodean continent caused cartographers to override the information brave explorers brought back from their ventures. When Magellan made the dangerous crossing from Atlantic to Pacific off the tip of South America, they spotted Tierra del Fuego and surmised it was an island. Cartographers, however, chose to override those who had been there, and drew Tierra del Fuego as an outcropping of the great continent. More mapmakers embellished their maps with prominent features like the land of Parrots, the Cape of Good Signal and the River of Islands, all lending credence to the existence on the continent. But exploration in the Pacific continued to chip away at the continent’s size, but it was only in the 1770s, when Captain James Cook was instructed to search for the southern continent, that he sailed farther south than 71 degrees to a land of fog and snow mists, that cartographer’s gave up on their belief in the super-sized southern continent.

So they turned their notion of symmetry northward.

If South America and Africa both had southern straights that gave passage from one ocean to another, then surely there must be something similar in the north. This led to the search for the Northwest Passage that scattered the names of many an explorer across Canada’s north. Think Frobisher Bay. Think Baffin Island and Hudson Bay, just to name a few.

Explorers from Spain, France and England sent explorers up and down the coast of North America and deep inland through the great lakes, seeking that passage. The English sent exploration teams one after another into Canada’s north, many never to be heard from again.

When the search from east to west brought no results, they sent famed Captain Cook, and then Captain Vancouver, exploring and mapping the Pacific coast of North America still seeking that elusive fjord that would spread out and become a fulsome channel all the way to England.

It was not to be, but such legends died hard. And today perhaps the ancient Greeks are laughing, as global warming opens up the northern passage they prophesized. Symmetry exists at last.

The story continues for Jaymee and David Corbin, and of course things get worse. To read on, click HERE.

The story continues for Jaymee and David Corbin, and of course things get worse. To read on, click HERE.

I mentioned last week how the ancient Egyptian, Eratosthrenes, used a column and a shadow as two sides of a triangle to estimate the size of the earth, which shows the importance of geometry to cartography. Nowhere was this more evident than in mapping the earth, where triangulation, (the process of determining the location of a point by measuring angles to an unknown point from known points at either end of a fixed baseline), was literally used to measure the location of everything in relation to everything else.

I mentioned last week how the ancient Egyptian, Eratosthrenes, used a column and a shadow as two sides of a triangle to estimate the size of the earth, which shows the importance of geometry to cartography. Nowhere was this more evident than in mapping the earth, where triangulation, (the process of determining the location of a point by measuring angles to an unknown point from known points at either end of a fixed baseline), was literally used to measure the location of everything in relation to everything else.

Geometry and triangulation had actually proven themselves previous to Eratosthrenes. They’d been used to measure the heights of the pyramids and had also had been highlighted by the ancient Chinese as an important principle of mapmaking. Unfortunately this wasn’t well known in Europe even though the Arabic influence brought such surveying methods into old Spain. Instead, Europe was still transcribing tourist tales and fanciful stories onto paper and selling these for parlor display based on their beautiful illuminations, rather than spending their time surveying the landscape.

Apparently the first European to get serious about the use of triangulation was a Dutchman named Gemma Frisius who suggested using triangulation as a means to pinpoint the location of places on maps. The technique gradually spread through the 1500s, but it wasn’t until the 1600s that Europe got serious. A Dutchman named Snell began the process of surveying the landscape with a chained line of triangles (much like the triangles the American flag is folded into)across the countryside for a distance of 70 miles. The use of Snell’s process led to a rise in the quality of the Dutch maps and, in comparison, the decline of French maps into dependence upon engraving and elegant color as their selling feature – all well and good as a parlor adornment, but not what you want if you actually want to do something with the map you made.

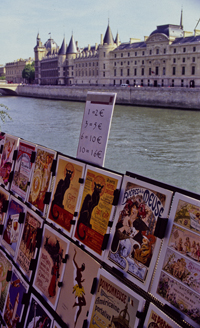

Enter Guillaume Deslisle: In the late 1600s this young Frenchman began to change maps from things of the arts to matters of science. At a time when the great rulers such as Louis XIV knew little about the countries they ruled, he began to use triangulation surveys to permanently shift and fix continents and islands on the map, and even settled the age-old argument about the length of the Mediterranean Sea (41 degrees). The work of Deslisle and his kin led to the first mapping of Russia, or Muscovia as it was known at the time, and eventually influenced the French Minister for Home Affairs and advisor to Louis the XIV, Jean Colbert, to push for the mapping of France.

Enter Guillaume Deslisle: In the late 1600s this young Frenchman began to change maps from things of the arts to matters of science. At a time when the great rulers such as Louis XIV knew little about the countries they ruled, he began to use triangulation surveys to permanently shift and fix continents and islands on the map, and even settled the age-old argument about the length of the Mediterranean Sea (41 degrees). The work of Deslisle and his kin led to the first mapping of Russia, or Muscovia as it was known at the time, and eventually influenced the French Minister for Home Affairs and advisor to Louis the XIV, Jean Colbert, to push for the mapping of France.

In 1663, Colbert ordered that each French province’s maps be examined to see if they were of sufficient quality. If they were not, qualified surveys were to be undertaken. This eventually led to Abbe Jean Picard overseeing the first precisely measured chain of triangles and topographical surveys around Paris – the two preliminary foundations to accurate mapping. The extension of this process led to France being mapped and became the standard practice for scientific mapmakers. It was used in the cartographic expeditions used in Lapland and Peru discussed in my last cartographic blog, in mapping the Himalayas, the English countryside and, the Grand Canyon and everywhere else in the world.

In 1663, Colbert ordered that each French province’s maps be examined to see if they were of sufficient quality. If they were not, qualified surveys were to be undertaken. This eventually led to Abbe Jean Picard overseeing the first precisely measured chain of triangles and topographical surveys around Paris – the two preliminary foundations to accurate mapping. The extension of this process led to France being mapped and became the standard practice for scientific mapmakers. It was used in the cartographic expeditions used in Lapland and Peru discussed in my last cartographic blog, in mapping the Himalayas, the English countryside and, the Grand Canyon and everywhere else in the world.

But the work of Deslisle and Picard had unforeseen impacts. Like the magic in my books, the new maps seriously revised France’s boundaries and coastal outline. The world’s shape was changed again – all because of three points.

But the work of Deslisle and Picard had unforeseen impacts. Like the magic in my books, the new maps seriously revised France’s boundaries and coastal outline. The world’s shape was changed again – all because of three points.

Free fiction Wednesday continues the urban fantasy thriller of shapeshifter Jaymee Gray and her immortal lover. Click Here.